Brussels, 17 February 2025

Edited By: Giuseppe Spatafora

According to a recent survey of European experts, withdrawal from Europe by the United States would be as destabilising for the EU as a nuclear attack by Russia(1). With the return of President Donald Trump, their concerns could soon become a reality. The new administration’s initial policies – negotiating with Russia without involving Ukraine or EU allies, expecting European countries to enforce a future agreement without US backing, and attacking the EU on trade, technology and freedom of speech – raise concerns about the reliability of the US as an ally, the EU Institute for Security Studies writes in its latest brief.

However, abandonment of Europe could still entail multiple scenarios. On the one hand, Trump may see abandonment as a policy goal: the US should shift focus to the defence of the US homeland and the challenge posed by China. This would result in the progressive reduction of US forces in Europe.

On the other hand, Trump could use the threat of abandonment as a bargaining chip to force allies to spend more on US weapons, or to gain concessions in other areas such as trade and technology standards. This could result in the bilateralisation and fragmentation of defence ties between Washington and European capitals.

This Brief presents the two scenarios outlined above and their policy implications. It argues that the reality will likely include elements of both scenarios, and that the EU should be prepared for both. The best way to do so is to invest in a strong European deterrent force.

A whole new game

During his first tenure at the White House, Trump was the most outspoken critic of European under-investment in defence. In 2018, he came dangerously close to withdrawing the US from NATO if allies did not meet their 2% defence spending pledge(2). But he also maintained the traditional US opposition to European defence initiatives outside the transatlantic framework. In 2019, the US sent a letter to HR/VP Federica Mogherini complaining that Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) and the European Defence Fund (EDF) discriminated against American defence companies(3).

Trump’s return has elevated fears about the future of the transatlantic relationship to a new level.

Trump’s return to the presidency in 2025 has elevated fears about the future of the transatlantic relationship to a new level. On the 2024 campaign trail, Trump ramped up this threat, claiming that he would not protect European allies who do not spend enough on defence. Sumantra Maitra, a Trump advisor, proposed the model of a ‘dormant’ NATO, in which the US commitment to Europe would be stripped down: the alliance would be ‘put on ice, only to be activated in times of crisis’(4).

But the set of challenges to the transatlantic relationship goes beyond defence. Trump has threatened to annex the territory of allied countries. The US is imposing across-the-board tariffs that will likely hurt Europeans. He has started negotiating an end to the Ukraine war with Putin, heightening fears that he might make concessions behind Europe’s back. At the Munich Security Conference, Vice-President JD Vance accused the EU of censoring free speech. In the past, Vance even suggested withdrawing from NATO if the EU tries to regulate US companies(5).

As these initial actions suggest, the Trump 2.0 administration will not hesitate to use all the instruments at its disposal to advance US interests, even against long-standing allies. As President Zelensky warned in his speech at the Munich Security Conference: ‘We can’t rule out the possibility that America might say “no” to Europe on issues that threaten it’(6).

A tale of two futures

Trump’s aggressive rhetoric and actions suggest that US abandonment of Europe is now on track to materialise. However, the way this threat manifests in policy could vary significantly.

Take tariffs as a useful comparison. According to advisors such as Peter Navarro, tariffs should become a permanent feature of US policy – for instance, to remove China from specific value chains, or to encourage domestic consumption. However, the US has also deployed tariffs for bargaining purposes. For instance, Trump imposed tariffs on Colombia, Canada and Mexico, only to withdraw them after obtaining concessions in countering fentanyl flows or accepting migrant repatriations.

For Trump, abandonment could be a policy goal or a bargaining chip.

Much like tariffs, US policy on Europe could take different forms: for Trump, abandonment could be a policy goal or a bargaining chip. Each interpretation entails vastly different scenarios. Ultimately, US policy will likely reflect aspects of both strategies. The Trump coalition contains advocates of both interpretations of disengagement. The president himself is not new to U-turns: he could shift between the pursuit of abandonment as a goal and its use as bargaining chip.

Scenario 1: ‘Tit for tat.’

In this scenario, Trump 2.0 pursues a transactional approach to European defence, using the threat of abandonment as leverage. In this interpretation, the US does not aim to ultimately disengage from Europe, but threatens to do so to push European countries to increase their share of the defence burden. However, allies are not free to spend anywhere but must privilege US assets and weapons. The US also uses the threat of abandonment if Europeans do not make concessions in other areas, such as changing technology standards to benefit American companies.

Faced with these pressures, European states try to placate Trump by increasing defence spending, accepting compromises in other areas and signing new contracts with American companies. The US then reassures compliant allies through bilateral deals (e.g. by putting troop withdrawal plans on hold), while taking punitive action and escalating threats against those who do not spend enough. This scenario could lead to the pure bilateralisation of defence relationships: the US would deal bilaterally (or in small groupings) with European countries, playing on existing divergences among Member States.

This scenario aligns with the US’s long-term stance of remaining embedded in Europe’s security architecture, although it places a premium on relations with individual allies rather than on the entire alliance. It echoes some of Trump’s actions during his first term, when he chastised allies for not spending enough on defence or excluding US contractors, while rewarding those who spent a lot on US assets – such as by promising a major American base (like the planned but never completed ‘Fort Trump’ in Poland)(7). Trump seems to be repeating this playbook with Ukraine, seeking to extract concessions from Kyiv on critical minerals.

This scenario is compatible with the position of more traditional Republicans within the administration and Congress. The US maintains strong defence industrial ties with European allies, which creates a relevant constituency interested in continuing to sell weapons to Europe. It also reflects the preference of many European states who favour maintaining ties with the US defence industrial base over developing independent European capabilities.

Scenario 2: ‘So long Europe.’

In another scenario, the US pursues a strategic retrenchment from Europe to prioritise other theatres. Conventional US assets in Europe (vessels, long-range missiles, tactical aircraft and forward-based troops) and command and control capabilities are moved to other priority areas, such as the defence of the US homeland or the Indo-Pacific. The US also seeks to quickly disengage from conflicts in the region such as the war in Ukraine, brokering a hasty ceasefire and leaving Europeans in charge of enforcing it.

On the defence industrial side, the Pentagon revises production and procurement decisions to meet the needs of naval warfare in the Pacific over land warfare in Europe. The Department of Defense (DoD) prioritises foreign military sales to Indo-Pacific countries over deliveries to Europeans(8). While American disengagement from Europe could take years, giving the Europeans time to adjust, this scenario could swiftly materialise in the event of a crisis elsewhere – or if Trump wanted to obtain a quick domestic success.

This scenario is consistent with the Trump campaign’s promise to transform NATO and shift the burden of conventional deterrence entirely on European shoulders. Project 2025, the administration’s ideological blueprint, argues that US allies should be ‘capable of fielding the great majority of the conventional forces required to deter Russia while relying on the United States primarily for our nuclear deterrent’(9). This position has advocates among high-level officials within the DoD, including Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth, who argue that the US does not possess the resources to fight a two-front war with Russia and China, and should prioritise the systemic challenge posed by China over the security needs of Europeans(10).

Preparing for all possibilities

As mentioned above, reality will likely contain elements of both scenarios. Europeans cannot just rely on one interpretation of abandonment. Some countries will seek to appease Trump by buying more US weapons or signing side deals, but that will not solve the issue if the administration’s goal is to disengage from Europe. To prepare for all contingencies, the EU should develop a more balanced strategy. At its core, this strategy would entail the creation of a strong European deterrent force that could make up for US retrenchment.

First, Brussels should support Member States in enhancing defence spending, through the best available means – such as a special purpose vehicle or collective borrowing. Higher resources for defence spending will increase Europeans’ bargaining power at the NATO Summit, demonstrating to Trump that Europeans are serious about defending themselves. It will also enable Europeans to take primary responsibility for providing security assistance to Ukraine.

Second, the EU should support the development of collective capabilities at European level: these include strategic enablers – strategic airlift, air-to-air refuelling, operational intelligence and air defences – that are necessary to transform capabilities into active fighting power. So far, the bulk of these capabilities has been provided by the US. But if Trump decides to withdraw them – either to obtain concessions or because they are needed in other theatres – the impact on European deterrence would be significant.

While Member States should remain free to spend their domestic defence budgets as they please, the collective funds raised by the EU should prioritise investments in these collective capabilities. The EU should involve non-EU NATO allies in Europe and Ukraine in these projects as much as possible. The sharing of classified information between the EU and NATO will be essential to develop assets that effectively support the execution of European defence plans.

Third, the EU should support Member States in developing the necessary resources for conventional deterrence. As the war in Ukraine has shown, contemporary high-intensity warfare requires an enormous number of expendable products such as artillery and unmanned systems, as well as large armies. The US armed forces are far ahead of their European allies in these metrics. Continuing to support Ukraine and deterring Russia in the absence of the US would only be possible if the Europeans produce weapons at the necessary scale and have large and battle-ready armed forces. In addition, European societies must be ready to absorb the shock of both hybrid and conventional attacks.

Conclusion

The prospect of abandonment by a second Trump administration while war rages on Europe’s borders poses a vital challenge to our security. The EU must develop a comprehensive strategy to address all possible scenarios. The only viable response is to invest in Europe’s security – across all dimensions. It will take time and will not be easy. But it needs to be done.

Read the EU-ISS brief

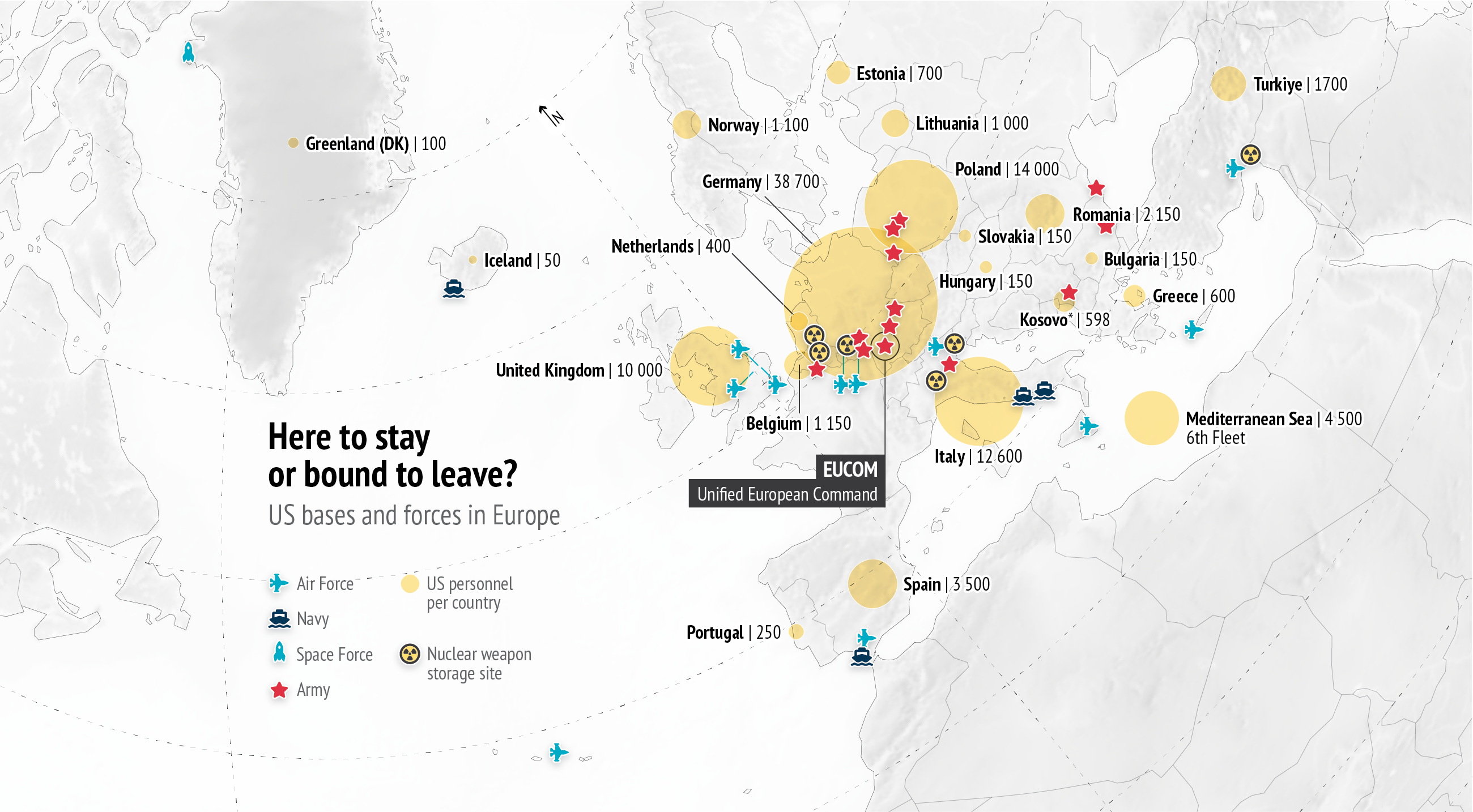

*NOTE: The EU-ISS map related to this post is based on data by: European Commission, GISCO, 2025; US Army, 2025; IISS, The Military Balance, 2025; CSIS, 2024; CFR, 2023

References

- Anghel, V. and Spatafora, G., ‘Global Risks to the EU: A blueprint to navigate the year ahead’, EUISS Commentary, 6 February 2025 (https://www.iss.europa.eu/publications/commentary/global-risks-eu-bluep…).

- Foy, H., ‘The untold story of the most chaotic Nato summit ever’, Financial Times, 4 July 2024 (https://www.ft.com/content/8985b970-0015-479f-9585-7a9b234715a4).

- ‘Letter from US Undersecretary of Defense Lord and US Undersecretary of State Thompson to HRVP Mogherini’, New York Times, 1 May 2019 (https://int.nyt.com/data/documenthelper/1073-19-5-1-02-letter-to-hrvp-m…).

- Maitra, S., ‘The path to a “dormant NATO’’’, The American Conservative, 29 December 2023 (https://www.theamericanconservative.com/the-path-to-a-dormant-nato/).

- Kilander, G., ‘JD Vance says US could drop support for NATO if Europe tries to regulate Elon Musk’s platforms’, The Independent, 17 September 2024 (https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/jd-vance-…).

- Hodunova, K., ‘“Putin is weak. We must use that”— Zelensky’s Munich speech in 5 key quotes’, Kyiv Independent, 15 February 2024 (https://kyivindependent.com/zelenskys-munich-speech-in-5-key-quotes/).

- Plucinska, J. and Ali, I., ‘U.S.-Polish Fort Trump project crumbles’, Reuters, 19 June 2020 (https://www.reuters.com/article/world/us-polish-fort-trump-project-crum…).

- Donnelly, J., ‘Trump’s picks for Pentagon team spark GOP debate on security’, 6 February 2025 (https://rollcall.com/2025/02/06/trumps-picks-for-pentagon-team-spark-go…).

- Dans, P. and Groves, S. (eds.), Mandate for Leadership: the Conservative Promise–Project 2025, The Heritage Foundation, 2022, p. 94 (https://static.project2025.org/2025_MandateForLeadership_FULL.pdf).

- Colby, E., The Strategy of Denial: American defense in an age of great power conflict, Yale University Press, 2022; Sabbagh, D., ‘US no longer “primarily focused” on Europe’s security, says Pete Hegseth’, The Guardian, 12 February 2025 (https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2025/feb/12/us-no-longer-primarily-…).