Stockholm, 17 June 2024

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) today launches its annual assessment of the state of armaments, disarmament and international security. Key findings of SIPRI Yearbook 2024 are that the number and types of nuclear weapons in development have increased as states deepen their reliance on nuclear deterrence.

Nuclear arsenals being strengthened around the world

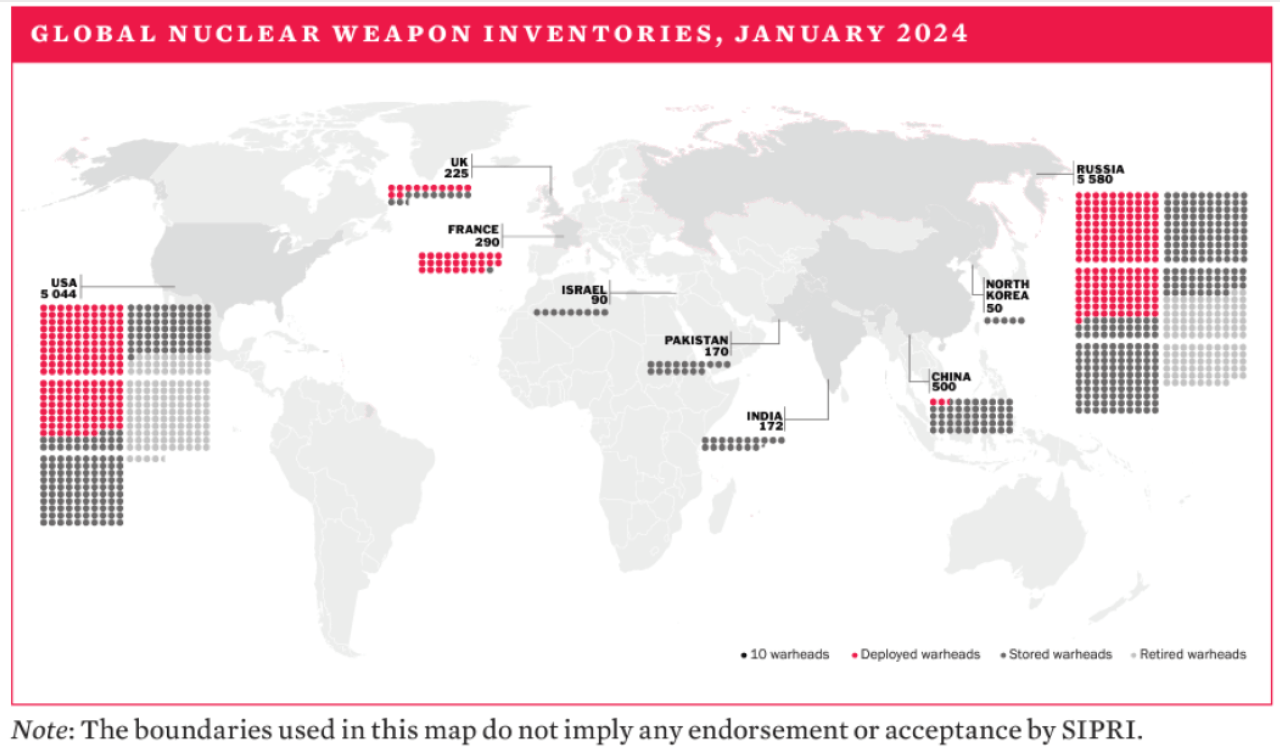

The nine nuclear-armed states—the United States, Russia, the United Kingdom, France, China, India, Pakistan, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (North Korea) and Israel—continued to modernize their nuclear arsenals and several deployed new nuclear-armed or nuclear-capable weapon systems in 2023.

Of the total global inventory of an estimated 12,121 warheads in January 2024, about 9,585 were in military stockpiles for potential use (see the table below). An estimated 3904 of those warheads were deployed with missiles and aircraft—60 more than in January 2023—and the rest were in central storage. Around 2100 of the deployed warheads were kept in a state of high operational alert on ballistic missiles. Nearly all of these warheads belonged to Russia or the USA, but for the first time China is believed to have some warheads on high operational alert.

‘While the global total of nuclear warheads continues to fall as cold war-era weapons are gradually dismantled, regrettably we continue to see year-on-year increases in the number of operational nuclear warheads,’ said SIPRI Director Dan Smith. ‘This trend seems likely to continue and probably accelerate in the coming years and is extremely concerning.’

India, Pakistan and North Korea are all pursuing the capability to deploy multiple warheads on ballistic missiles, something Russia, France, the UK, the USA and—more recently—China already have. This would enable a rapid potential increase in deployed warheads, as well as the possibility for nuclear-armed countries to threaten the destruction of significantly more targets.

Russia and the USA together possess almost 90 per cent of all nuclear weapons. The sizes of their respective military stockpiles (i.e. useable warheads) seem to have remained relatively stable in 2023, although Russia is estimated to have deployed around 36 more warheads with operational forces than in January 2023. Transparency regarding nuclear forces has declined in both countries in the wake of Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and debates around nuclear-sharing arrangements have increased in saliency.

Notably, there were several public claims made in 2023 that Russia had deployed nuclear weapons on Belarusian territory, although there is no conclusive visual evidence that the actual deployment of warheads has taken place.

In addition to their military stockpiles, Russia and the USA each hold more than 1200 warheads previously retired from military service, which they are gradually dismantling.

SIPRI’s estimate of the size of China’s nuclear arsenal increased from 410 warheads in January 2023 to 500 in January 2024, and it is expected to keep growing. For the first time, China may also now be deploying a small number of warheads on missiles during peacetime. Depending on how it decides to structure its forces, China could potentially have at least as many intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) as either Russia or the USA by the turn of the decade, although its stockpile of nuclear warheads is still expected to remain much smaller than the stockpiles of either of those two countries.

‘China is expanding its nuclear arsenal faster than any other country,’ said Hans M. Kristensen, Associate Senior Fellow with SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Director of the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists (FAS). ‘But in nearly all of the nuclear-armed states there are either plans or a significant push to increase nuclear forces.’

Although the UK is not thought to have increased its nuclear weapon arsenal in 2023, its warhead stockpile is expected to grow in the future as a result of the British government’s announcement in 2021 that it was raising its limit from 225 to 260 warheads. The government also said it would no longer publicly disclose its quantities of nuclear weapons, deployed warheads or deployed missiles.

In 2023 France continued its programmes to develop a third-generation nuclear-powered ballistic missile submarine (SSBN) and a new air-launched cruise missile, as well as to refurbish and upgrade existing systems.

India slightly expanded its nuclear arsenal in 2023. Both India and Pakistan continued to develop new types of nuclear delivery system in 2023. While Pakistan remains the main focus of India’s nuclear deterrent, India appears to be placing growing emphasis on longer-range weapons, including those capable of reaching targets throughout China.

North Korea continues to prioritize its military nuclear programme as a central element of its national security strategy. SIPRI estimates that the country has now assembled around 50 warheads and possesses enough fissile material to reach a total of up to 90 warheads, both significant increases over the estimates for January 2023. While North Korea conducted no nuclear test explosions in 2023, it appears to have carried out its first test of a short-range ballistic missile from a rudimentary silo. It also completed the development of at least two types of land-attack cruise missile (LACM) designed to deliver nuclear weapons.

‘Like several other nuclear-armed states, North Korea is putting new emphasis on developing its arsenal of tactical nuclear weapons,’ said Matt Korda, Associate Researcher with SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme and Senior Research Fellow for the Nuclear Information Project at the Federation of American Scientists. ‘Accordingly, there is a growing concern that North Korea might intend to use these weapons very early in a conflict.’

Israel—which does not publicly acknowledge possessing nuclear weapons—is also believed to be modernizing its nuclear arsenal and appears to be upgrading its plutonium production reactor site at Dimona.

Tensions over Ukraine and Gaza wars further weaken nuclear diplomacy

Nuclear arms control and disarmament diplomacy suffered more major setbacks in 2023. In February 2023 Russia announced it was suspending its participation in the 2010 Treaty on Measures for the Further Reduction and Limitation of Strategic Offensive Arms (New START)—the last remaining nuclear arms control treaty limiting Russian and US strategic nuclear forces. As a countermeasure, the USA has also suspended sharing and publication of treaty data.

In November Russia withdrew its ratification of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty (CTBT), citing ‘an imbalance’ with the USA, which has failed to ratify the treaty since it opened for signature in 1996. However, Russia confirmed that it would remain a signatory and would continue to participate in the work of the Comprehensive Nuclear-Test-Ban Treaty Organization (CTBTO). Meanwhile, Russia has continued to make threats regarding the use of nuclear weapons in the context of Western support for Ukraine. In May 2024 Russia carried out tactical nuclear weapon drills close to the Ukrainian border.

‘We have not seen nuclear weapons playing such a prominent role in international relations since the cold war,’ said Wilfred Wan, Director of SIPRI’s Weapons of Mass Destruction Programme. ‘It is hard to believe that barely two years have passed since the leaders of the five largest nuclear-armed states jointly reaffirmed that “a nuclear war cannot be won and must never be fought”.’

An informal agreement reached between Iran and the USA in June 2023 seemed to temporarily de-escalate tensions between the two countries, which had intensified over Iran’s military support to Russian forces in Ukraine. However, the start of the Israel–Hamas war in October upended the agreement, with proxy attacks by Iran-backed groups on US forces in Iraq and Syria apparently ending Iranian–US diplomatic efforts. The war also undermined efforts to engage Israel in the Conference on the Establishment of a Middle East Zone Free of Nuclear Weapons and Other Weapons of Mass Destruction.

More positively, the June 2023 visit to Beijing by the US secretary of state, Antony Blinken, seems to have increased space for dialogue between China and the USA on a range of issues, potentially including arms control. Later in the year the two sides agreed to resume military-to-military communication.

Global security and stability in increasing peril

The 55th edition of the SIPRI Yearbook analyses the continuing deterioration of global security over the past year. The impacts of the wars in Ukraine and Gaza are visible in almost every aspect of the issues connected to armaments, disarmament and international security examined in the Yearbook. Beyond these two wars—which took centre stage in global news reporting, diplomatic energy and discussion of international politics alike—armed conflicts were active in another 50 states in 2023. Fighting in the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Sudan saw millions of people displaced, and conflict flared up again in Myanmar in the final months of 2023. Armed criminal gangs were a major security concern in some Central and South American states, notably leading to the effective collapse of the state in Haiti during 2023 and into 2024.

‘We are now in one of the most dangerous periods in human history,’ said Dan Smith, SIPRI Director. ‘There are numerous sources of instability—political rivalries, economic inequalities, ecological disruption, an accelerating arms race. The abyss is beckoning and it is time for the great powers to step back and reflect. Preferably together.’

In addition to the usual detailed coverage of nuclear arms control, disarmament and non-proliferation issues, the SIPRI Yearbook presents data and analysis on developments in world military expenditure, international arms transfers, arms production, multilateral peace operations, armed conflicts and more. Special sections in SIPRI Yearbook 2024 explore the role of Russian private military and security companies in conflicts; efforts to reduce the peace and security risks related to artificial intelligence, outer space and cyberspace; and issues around the protection of civilians in the wars in Gaza and Ukraine.

Notes

The SIPRI Yearbook is a compendium of cutting-edge information and analysis on developments in armaments, disarmament and international security. Three major SIPRI Yearbook 2024 data sets were pre-launched in 2023–24: total arms sales by the top 100 arms-producing companies (December 2023), international arms transfers (March 2024) and world military expenditure (April 2024). The SIPRI Yearbook is published by Oxford University Press. Learn more at www.sipriyearbook.org.

Contents

- 1. Introduction: International stability and human security in 2022

- 2. Trends in armed conflicts

- 3. Multilateral peace operations

- 4. Private military and security companies in armed conflict

- 5. Military expenditure and arms production

- 6. International arms transfers

- 7. World nuclear forces

- 8. Nuclear disarmament, arms control and non-proliferation

- 9. Chemical, biological and health security threats

- 10. Conventional arms control and regulation of new weapon technologies

- 11. Space and cyberspace

- 12. Dual-use and arms trade controls

- Annexes

Summaries

- Arabic (Centre for Arab Unity Studies)

- Japanese (Waseda University Tago Laboratory)

- Russian (SIPRI)

- Chinese, Simplified (SIPRI)

- Korean (PEACEMOMO)

- Ukrainian (Razumkov Centre (Ukrainian Centre for Economic and Political Studies))

- Dutch (Vlaams Vredesinstituut)

- Italian (Torino World Affairs Institute)

- Swedish (SIPRI)

- Spanish (FundiPau)

- French (GRIP)

- Catalan (FundiPau)

- English (SIPRI)

Related files

- Press release (Catalan)

- Press release (French)

- Press release (Spanish)

- Press release (Swedish)

- Click here to download the sample chapter of SIPRI Yearbook 2024 on world nuclear forces.

Related issues

Source – SIPRI