Washington DC, 16 July 2024

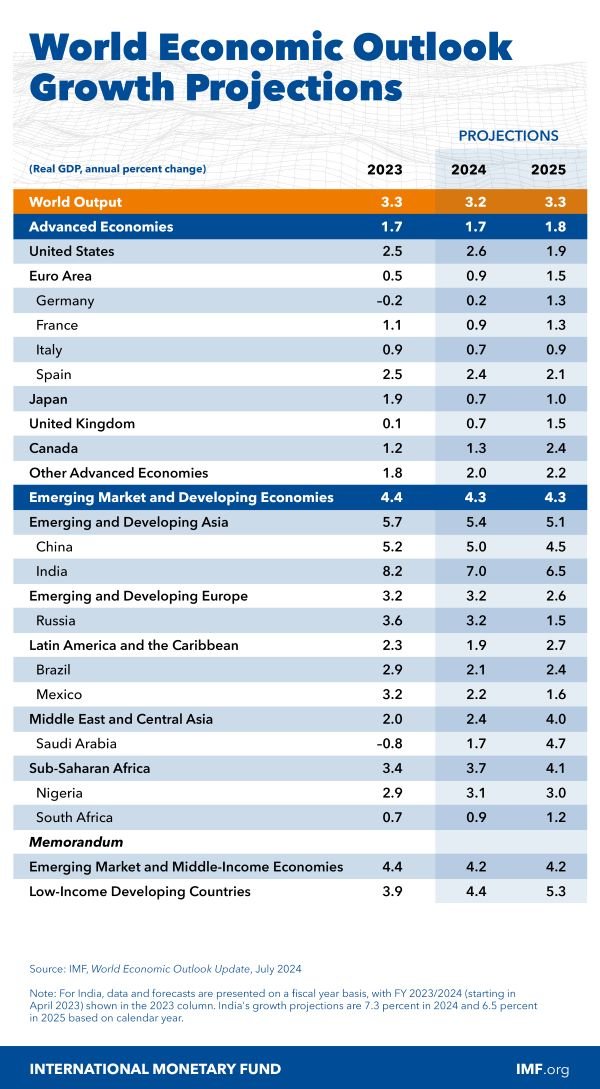

Global growth is projected to be in line with the April 2024 World Economic Outlook (WEO) forecast, at 3.2 percent in 2024 and 3.3 percent in 2025.

Services inflation is holding up progress on disinflation, which is complicating monetary policy normalization. Upside risks to inflation have thus increased, raising the prospect of higher for even longer interest rates, in the context of escalating trade tensions and increased policy uncertainty. The policy mix should thus be sequenced carefully to achieve price stability and replenish diminished buffers.

Press Conference On Release of the July 2024 World Economic Outlook Update

July 16, 2024

***

***

PARTICIPANTS:

Moderator:

JOSE LUIS DE HARO, Communications Department

Panelists:

- PIERRE-OLIVIER GOURINCHAS, Economic Counselor and Director, Research Department

- JEAN-MARC NATAL, Division Chief, Research Department

- PETYA KOEVA BROOKS, Deputy Director, Research Department

DE HARO: So good morning everyone, and welcome to this virtual Press Briefing. I’m Jose Luis de Haro with the Communications Department here at the International Monetary Fund, and we are gathered here today for the launch of the World Economic Outlook Update. I hope that by this time you all have access to the document. If not, I will encourage you to go to imf.org. There you will find the flagship, but also Pierre-Olivier’s blog and other assets that might be helpful for your reporting.

And to discuss the World Economic Outlook Update today, we are joined by Pierre-Olivier Gourinchas. He is the Chief Economist and the Director of the Research Department. Next to him are Petya Koeva Brooks, she is the Deputy Director of the Research Department. And also with us today, Jean-Marc Natal, he is Division Chief with the Research Department. Pierre-Olivier is going to start with some opening remarks, and then we will proceed to take your questions.

But I want to remind everyone a little bit about the World Economic Outlook cycle. The updates do nothing include a full set of countries. The full set it’s only included during our World Economic Outlooks that are launched in the Spring Meetings in April and in the Annual Meetings in October. So the updates that we launch in January and in July only include a limited set of countries. But obviously we include our outlook for the global economy, the risks to the baseline, and of course, our policy recommendations. Let me stop here and Pierre-Olivier, the floor is yours.

GOURINCHAS: Thank you, Jose, and good morning everyone. Global growth remains steady at 3.2 percent this year, unchanged from our April World Economic Outlook, and slightly higher at 3.3 percent next year. But there have been some notable developments since April.

First, growth in major advanced economies is becoming more aligned as output gaps are closing. In the United States, we see increasing signs of cooling. In the euro area, meanwhile, growth is picking up. Asia’s emerging market economies remain the main engine for the global economy. Growth in India and China is revised upwards and accounts for almost half of global growth. Yet prospects for the next five years remain weak. Growth in China is projected to moderate to 3.3 percent by 2029, well below its current pace.

As in April, global inflation was slow to 5.9 percent this year from 6.7 percent last year, broadly on track for a soft lending. But in some advanced economies, especially the United States, progress on disinflation has slowed. Risks remain broadly balanced, but some downside near-term risks have gained in prominence.

First, there could be bumps on the disinflation path in advanced economies. This could force central banks, including the Federal Reserve, to keep borrowing costs higher for even longer that would put overall growth at risk, with increased upward pressure on the dollar and harmful spillovers to emerging and developing economies. Mounting empirical evidence points to the importance of global headline inflation shocks, mostly energy and food prices, in driving the inflation surge and subsequent decline across a broad range of countries.

The good news is that ahead as headline inflation shocks receded, inflation came down without a recession. The bad news is that energy and food price inflation are now almost back to pre-Pandemic levels in many countries. While overall inflation is not yet one reason, as we emphasized previously, is that goods prices remain high relative to services. Unless goods inflation declines further, pressure on services prices and wages may keep overall inflation higher than desired.

This remains a significant risk to the soft lending scenario. This means that monetary policy must remain vigilant, avoiding a premature easing, especially where the economy remains strong, but also avoiding excessive delays once inflation is decisively on its way back toward targets.

Second, fiscal challenges need to be tackled more directly. In many countries, public finances have deteriorated more than foreseen before the Pandemic, leaving them more vulnerable. Gradually and credibly rebuilding buffers while still protecting the most vulnerable is a critical priority. Doing so will free resources to address emerging spending needs, such as the climate transition or national and energy security.

Stronger buffers also provide the necessary policy space to address unexpected shocks. Unfortunately, projected fiscal consolidations are largely insufficient in too many countries, and this magnifies economic policy and certainty. For instance, it is concerning that the United States, while at full employment, maintains a fiscal stance that pushes its debt-to-GDP ratio steadily higher, increasingly relying on short-term funding with risks to both the domestic and global economy.

Third, the gradual dismantling of our multilateral trading system is another key concern. More countries are now going their own way, imposing unilateral tariffs or industrial policy measures. Our imperfect trading system must be improved. But this surge in unilateral measures isn’t likely to deliver lasting and shared global prosperity. If anything, it will distort trade and resource allocation, spur retaliation, weaken growth, and make it harder to coordinate policies that address global challenges, such as the climate transition.

Trade instruments have their legitimate place in the policy arsenal, but because international trade is not a zero sum game, they should always be used, apparently within a multilateral framework, and to correct well-identified distortions. Unfortunately, we find ourselves increasingly at a remove from these basic principles. Constructive multilateral cooperation remains the only way to ensure a safe and prosperous economy for all.

Instead, we should focus on sustainably improving medium term growth prospects through more efficient allocation of resources within and across countries, better education opportunities and equality of chances. Faster and greener innovation and stronger policy frameworks. Thank you.

DE HARO: Thank you, Pierre-Olivier. And I want to set some ground rules before we open the floor to your questions. Please, if you want to ask a question, raise your virtual hand and wait till we call on you. Turn your camera on. And when we do, please identify yourself and the outlet that you represent. Also, I’m going to be asking some questions on behalf of reporters that they are sending those questions through the Press Center.

And of course, I want to remind everyone that we are here to discuss the World Economic Outlook Update. The countries that are in this report and any other countries that are not included here, and questions about program negotiations, about country programs, this is not the forum to tackle those, but you can send those questions to me bilaterally. And I’m happy to put you in touch with the right teams. So with this said, I think that we can start. And I see Colby Smith, Financial Times.

QUESTIONER: Thank you so much for doing this.

DE HARO: Go ahead, Colby.

QUESTIONER: And tied to the renewed trade tensions that you’ve mentioned and are highlighted in the report, I’m just curious what kind of protectionist policies specifically most concern the Fund. And what is your initial assessment of the economic impact potentially stemming from the 10 percent across-the-board tariffs proposed by the Republican nominee in the U.S., Donald Trump?

GOURINCHAS: Well, thank you, Colby. One concern we have, as I mentioned in my opening remarks, is that we see an explosion in a number of trade-restrictive measures. We’ve seen upwards of 3,000 such measures implemented in last year in 2023. This is up from 1,000 such measures in 2019. And 1,000 measures in 2019, that was not a low tide. That was already a high number. And so this takes the form of restrictions on exports. This takes the form of various industrial policy measures that have a trade component. And of course, this leads to retaliation. We see that when a country imposes trade restrictive measures, there are retaliation from other trading partners that are imposed in fairly short order, and that reduces or impacts trade, bilateral trade mostly at this point. And that can impact also the diffusion of knowledge, capital flows and increase uncertainty in the global economy, and leaves countries more vulnerable.

So one concern we have is that going forward, this will weigh down on global activity. Now, having said this, I should emphasize that in our Report, what we’re seeing for 2025, we’re seeing a fairly robust global growth in trade. So trade overall has not decoupled from economic activity, but we’re seeing a lot of rearrangement of the trade flows under the surface. At some point, this will start weighing down on economic activity.

DE HARO: Okay. I see Erwan Lucas from AFP, please go ahead.

QUESTIONER: Good morning. Thank you, Jose. Good morning, everyone. Erwan Lucas from AFP. I just had a quick question regarding the inflation. As you said, it’s a bit sticky still today. I would like to know if you had any idea of how would this impact the global economy in medium- and long-term, specifically maybe on middle-income country and lower-income country, and even more if the Fed keeps its rate at the current level even longer than anticipated. Thank you very much.

DE HARO: Pierre-Olivier, we have another kind of similar question from CNN. Which goes as follows: is the IMF concerned that the interest rate cuts by major central banks could cause inflation to search again? And also, is the IMF more or less optimistic about the Outlook?

GOURINCHAS: Yes. So inflation is, of course, one of the risks that we flag in our Update. We are concerned that the path of disinflation in some advanced economies had slowed down in the first part of the year. We got some good news in the U.S. with the June CPI Report. And so therefore, you know, it looks like inflation dynamics are moving, at least in the U.S., in the right direction. But we’ve seen bumps in the road, and we should anticipate that maybe there could be more and there could be some delays in the, the pace and the speed at which inflation will be coming down now.

So what risk does it pose to the global economy? Well, in response to this, central banks might need to stay higher for somewhat longer. Remember, back in January or in April, we’re expecting more cuts by the Federal Reserve, for instance, than where we are right now. In our Update, we’re anticipating there will be one cut by the Federal Reserve before the end of 2024. And, of course, the longer interest rate cuts are delayed or the higher the interest rate is in advanced economies, major currencies, that puts pressures on currencies, that put pressure on capital flows, and that pressure goes to emerging and middle-income and developing countries. So this is one concern for the global economy.

Now, are we concerned that central banks are cutting and this might lead to resurgence of inflation? Right now, what we’re seeing is we’re seeing very cautious action on the part of central banks, very careful in starting their cutting cycle. The ECB, the European Central Bank, has started its cutting cycle last month in June. Others have waited, and the Bank of England, for instance, and certainly the Federal Reserve. And so I think they are appropriately taking in all the data on making sure that this inflation path is solid, is secure, and it’s safe to actually start cutting interest rates.

DE HARO: Okay. Let me see, because you all appear in very, very tiny screens here in front of me. But I think I see Ramsey, Bloomberg.

QUESTIONER: Hi. Thanks, guys. I just wanted to follow up on the blog post. You mentioned the increasing U.S. reliance on short-term funding is also worrisome. Could you speak a little bit more about what those worries are specifically?

GOURINCHAS: Yes, I mean, of course, the worry here is that the more short-term funding you have in the structure of your debt, then the more often you need to go to the market and renew that funding. And so that increases potential vulnerabilities. If you think about a country that would have, will rely only on overnight funding, would need to, you know, renew its debt pretty much every day.

Now, to be clear, in the context of the U.S., we are not seeing at this point any vulnerability. There is no pressure. We can see the yields on U.S. debt are very stable. And so we are not concerned about this at this juncture. But we’re certainly wanting to flag that the direction of travel for U.S. public debt is one that is of concern. And the fact that the U.S. Treasury has moved towards more short-term finance reflects the fact that it’s also trying to, as it should, economize on the cost of funding. It’s usually a little bit cheaper at the short end of the curve, but it’s also a little bit riskier.

DE HARO: Okay, thank you, Pierre-Olivier. Let me see who — I think I see David Lawder, Reuters.

QUESTIONER: Hi. Hello. Thanks for the question. Just wanted to follow up on China in terms of its sort of weaker performance, which has come out since this particular analysis was closed the other day. They came out with weaker second quarter GDP numbers. Just wondering how concerned you are that this might lead to a push for even more exports to try to make up that gap of domestic consumption and therefore bring on, you know, the scenario of more trade restrictions that you described earlier. Thanks.

GOURINCHAS: Yes, thank you, David. So here on China, we had revised, in our Update, we’ve revised growth projections for 2024 and 2025. We’ve revised them up for China to 5 percent this year and to 4.6 percent, 4.5 percent next year. And this revision was in part based on stronger consumption numbers in the first quarter of the year, stronger exports also, and that lead us to that revision.

Now, the number that you refer to, the announcement about the second quarter growth numbers for China, came after we closed our projection round. And they indicate, in fact, that maybe growth in China, in particular consumer confidence and problems in the property sector, are still lingering. This is something that we had flagged. This is something we flag in our — in our data as a risk to the Chinese economy. And that seems to be perhaps materializing. So that’s something that we’ll take into account when we do our full set of projections in October.

Now, to the second part of your question, it is something that it is certainly the case that if there is weaker domestic demand on the side of the, you know, Chinese households and firms, then that will push more of the production towards the external sector and there will be more reliance potentially on the external sector.

Now, the Chinese economy has grown tremendously in the last 15-20 years, and it’s much less reliant overall on the external sector for its growth than it was maybe 15 years ago or 20 years ago. So here there is less of a concern, maybe from the Chinese perspective, but by the very fact that China is also bigger, it means it has a bigger footprint in the rest of the world. An increase in the trade surplus might be small from Chinese perspective, but it could be big from the perspective of the rest of the world. But on this, maybe to provide additional details on China, maybe, let me turn to Jean-Marc.

NATAL: Thank you, Pierre-Olivier. Maybe very quickly, to your question. As you know, we have revised growth in 2024 and 2025 for China from last year’s growth, from last April, growth by 0.4 in both years and for 2025. One of the reasons is that we expect that the new program, which is called trading and equipment upgrade, put in place by the Chinese authority, will help boost consumption and investment and growth at the same time. We have been recommending a shift towards consumption in the last few years, and this is one step in the right direction.

DE HARO: Thank you, Jean-Marc, Pierre-Olivier. We will get back to China, but first we’re going to go to the UK. Larry Elliot,.

QUESTIONER: Thank you very much indeed. Two things. One, I wonder whether you include the UK in the list of countries where you see service sector inflation being sticky, what that impact will be on the bank of England’s interest rates decisions. And secondly, a more general point. I mean, how do you view the position now of developing country debt and it’s — and how that’s progressing, given the increased protectionist pressures and the upward pressure on interest rates that you suggest might be happening in the rise in the dollar?

DE HARO: Pierre-Olivier, we have some other questions on the UK that I think we can tackle altogether. One is from Joel Hills from ITV News. What’s the impact, or what impact has the change of government in the UK? And then another one, it’s from Szu Chan from the Telegraph. Why have you upgraded your UK growth forecast?

GOURINCHAS: Yeah. So let me first address the question on services inflation. So certainly the UK, somewhat like the U.S. and other advanced countries, we’re seeing some persistence in services inflation, and that’s related to this persistence in overall inflation that we’ve seen. Services inflation has remained high. This is in the context in which wage growth also in a number of countries has been fairly robust. Now, some of that is catching up to the lost real incomes of the last few years, and so that’s also helping to support aggregate consumption because it improves the real income of households and improves purchasing power, and therefore that supports demand. But looking forward, we certainly see the UK in a situation that is in some ways similar to the U.S. when it looks — when you look at services inflation stickiness, if you want.

On the impact of the change in the government. Well, of course, the Fund doesn’t comment on election results. That’s the first point I want to make. The second is it’s too early for us to really assess the new policies that will be implemented by this new government. Although we do note that some of them are consistent with some of the recommendations that we have made in our, for instance, our most recent Article IV.

Finally, on the developing countries debt and the problems there. It’s certainly the case that many countries have been feeling a debt squeeze in the last few years. They’ve been having difficulties accessing the market. For many of them, it’s been difficult on the fiscal side because it leaves them with one less lever with which to try to meet the spending needs that they have. So it’s been a very challenging situation. A few countries have re accessed the market in 2024, but often at very elevated interest rates, sometimes in excess of 10 percent. So very costly access to funding.

So overall, the situation is challenging. We are not seeing a systemic debt crisis by far. We’re seeing some isolated situations that are challenging. And on the UK, maybe, Petya, did you want to?

BROOKS: No, I don’t have anything to add. Thank you.

DE HARO: So thank you, Pierre-Olivier. And now we’re going to stick to Europe. We’re going to Spain, winners of the Euro Cup and Wimbledon. Please, Carlos, come in.

QUESTIONER: Hello. Thank you so much for having me. And my question is, so is you have improved the growth of Spain in your report and also you say, the euro area, the services drive the recovery. So does the same applied to Spain or does this upgrade revision contains another factor besides the services? Thank you so much.

GOURINCHAS: Petya, would you like to.

BROOKS: Sure.

GOURINCHAS: Go ahead.

BROOKS: Spain is a bright spot in the euro area in terms of the revisions. We have upgraded the forecast for this year to 2.4. And a big part of that revision was due to the outturn that we saw in the first quarter of this year, where there was very strong services, exports, as well as a pickup in investment. But more broadly, the story in Spain remains what we had before. We are expecting real incomes to boost domestic demand as inflation comes down. And importantly, the EU funds, the new generation funds are also helping the outlook as well. I’ll stop here. Thank you.

DE HARO: Okay, we’re going to be changing regions. And now I think we go back to China. I see Maoling first and then Weier. So, Maoling, please go ahead and ask your question. Then Weier come in and ask her question.

QUESTIONER: Thank you, Host, thank you so much. It’s Maoling Xiong with Xinhua News Agency. I want to ask a follow up on the consumption issue that David asked. So how has China shift towards a consumption driven economy going? Do we expect this shift to continue and export to take a smaller portion of the GDP going forward just to more of a long-term perspective? Thank you.

GOURINCHAS: Jean-Marc, would you like to address.

NATAL: I can very quickly. So we expect consumption to resume at least in the next couple of years to the — to the level it was in terms of GDP before the Pandemic. It has been slowly catching up. For the future for the next few years, what we see is a slowdown that is due to more fundamental factors. Population growth and productivity growth will keep the economy — will slow the economy, and we expect the economy to grow by 3.3 percent by 2029.

DE HARO: Okay. I think that we go to Weier now.

QUESTIONER: Thank you, Jose. I actually have a question on the — in the report, you mentioned that the potential for a significant swings in economic policy as a result of the election this year, with negative spillover to the rest of the world, has increased the uncertainty around the baseline. So could you elaborate on these concerns, particularly in light of the upcoming U.S. election? Thank you.

GOURINCHAS: Yes. Well, we have, in 2024, we had a particularly election heavy year, and we’re already more than halfway through it. And what we are seeing is, of course, you know, as part of the Democratic process and elections, there can be some changes in general orientation or policies that can happen. And the uncertainty that is associated with that increases the overall policy uncertainty that we see overall. And so that’s one of the risks we flag.

And this is one risk we flag along two particular dimensions that are important to us. One is, as I’ve mentioned, a number of countries need to do some efforts on the fiscal side. They need to in an environment in which debt levels are higher, interest rates are higher, medium-term growth is lower, the debt dynamics are becoming more challenging. And so they need to make more efforts on their deficit side, reining in the deficits, making sure that they can bring in this debt-to-GDP ratios back to levels that give them some breathing room. And there is some concern about how much of that effort is going to be implemented, especially when there is policy uncertainty that might be associated with elections.

The second dimension is on the trade industrial policy side. We — there could be some increase in trade measures. There could be more distortions related to industrial policy measures. That could have spillovers to other countries, that could have an impact on the countries themselves. So let’s remember that when we look at the assessment of, for instance, the previous rounds of tariffs that have been imposed by countries, very often the cost assessment finds that it’s the country that imposes the tariffs that bears the cost of these tariffs. And so it hurts the domestic economy, and it also inflicts spillovers to other countries as well.

DE HARO: Okay, I see. Shu from JiJi Press. Please come in.

QUESTIONER: Thank you. Thank you very much for taking my question. And my question is on Japanese yen. Japanese yen had depreciated recently further, and there are some concerns on such development to adding pressure, especially on consumer sentiment. And what is your view on such ideas that BOJ, Bank of Japan, should hike its rate to contain such development, that is, further depreciation or devaluation of Japanese yen. Thank you.

GOURINCHAS: Well, the Japanese yen has indeed depreciated quite significantly since the, for instance, since the beginning of the year. It’s about 13 percent depreciation, the yen against the U.S. dollar since the beginning of the year, and even more if you look at the depreciation since 2022, for instance. So certainly, that’s something that has been impacting the Japanese economy.

Now, the Bank of Japan’s focus is on inflation and price stability. And what we’ve seen in Japan, and as we’ve seen that in many other countries, we’ve seen inflation increasing. But increasing, in the case of Japan, from levels that were extremely low when in fact, inflation for many, many years was well below the inflation target of the Bank of Japan. So now inflation is above the central bank target. The question is whether it will stay there or whether it will actually revert back to the very low inflation numbers that were in place before.

And I think this is the challenge that the Bank of Japan is facing. They’re starting normalizing monetary policy because they see that inflation is up and they need to adjust course, and they’ve signaled that they will be gradually tightening monetary policy. But the focus is not on stabilizing the exchange rate. The Japanese authorities are very committed to a flexible exchange rate regime. It’s more on ensuring price stability in the short- and medium-term.

Let me ask Jean-Marc if there are any additional points on the Japanese economy and inflation.

NATAL: No, I don’t have any more to add. Thank you.

DE HARO: Ok, so let me see who I see. Kemi, we please come in?

QUESTIONER: Me?

DE HARO: Yes.

QUESTIONER: Okay. Can you hear me?

DE HARO: Yeah, we can hear you loud and clear.

QUESTIONER: Yeah. Thank you very much for taking my question. Regarding your forecast for Africa, if you could provide additional information. As you know, a lot of focus is on the continent. In the next two, three decades, a lot of productivity innovation are expected to come from the continent. So investors are looking on the continent. On the other hand, we have a lot of shocks in countries across the continent, and majority of the average Africa are feeling the squeeze of high inflation. So I was wondering, what are your recommendations, and in terms, if you’re speaking to the — in lay terms, if you could provide information on how, regarding what you said, regarding capital flow, managing capital flow, how that will impact the average Africa. Thank you. And I have a follow up question.

DE HARO: Okay. We will try to get to you, Kemi, but we want to give everybody a chance to ask questions. I also have another question related to Sub-Saharan Africa from Godfrey Mutizwa, from CNBC Africa, that basically wants to know a little bit of the highlights and what’s new for the outlook for Sub-Saharan Africa.

GOURINCHAS: Yeah. So let me say just a word and then ask Jean-Marc to come in. So on Sub-Saharan Africa, the growth projections are for 2024, are revised downward a little bit to 3.7 percent, that’s a negative 0.1 percentage point revision, and are unchanged for 2025 at 4.1 percent. And the broad context here is that as we see inflation increasingly in the rearview mirror and we expect to see inflation in the rearview mirror. There is going to be an easing of global monetary conditions and financial conditions, and that is going to benefit also the region. But let me ask Jean-Marc to come in and provide more details.

NATAL: Yes, Pierre-Olivier. Growth is improving slowly in the region, but as you mentioned, the main issue is inflation for many of the countries in the region, and it comes from a cycle of depreciation and inflation, depreciation, inflation. And our recommendation in such cases is for monetary policy to tighten and stabilize inflation to achieve price stability in the medium-term, which will be a precondition for reestablishing fundamental conditions for growth in the country.

Now, of course, this policy may lead to impact on growth, and so it’s very important to also, at the same time, make sure that the most vulnerable are protected. And measures like in Nigeria, for example, the resumption of the cash transfers are actually the right move to — to safeguard the most vulnerable of the population.

GOURINCHAS: So if I can add something on this. I mean, the context is challenging for many countries in the region because of the funding squeeze that I mentioned already that is affecting a number of countries, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa. As we expect monetary conditions to ease an inflation to be brought under control, then that gradually will also — will also ease as well. So that will be a positive development.

But really, clearly, at the end of the day, what is very important for the — for the region is to put in place the conditions for sustained growth. And as you mentioned in your question, the continent has a tremendous number of assets. It’s a growth opportunity, and in particular, it has very favorable demographics. It has a population that is young, that is going to be a working age, that can certainly increase the outlook in that region. One of the challenges is going to be to bring skills and education and human capital to that population that is just willing and eager to engage in global economy.

DE HARO: Okay, I see a Abeer from Bloomberg. Please come in.

QUESTIONER: Hi, just Bloomberg, but thank you. So my question is about Saudi. And Saudi has gotten the biggest downgrade in its economic growth projections about one percentage point. So my question is about is, you know, does the IMF expect that Saudi or other GCC countries to allocate reserves as they invest more domestically? And the other part of that question is, if oil production cuts were to prolong further than what the government is estimating, do you think that Saudi is going to get further growth downgrades?

DE HARO: Please go ahead. And then we have another question in Egypt, but we can, we can go ahead.

GOURINCHAS: Well, let me turn over to Petya for Saudi Arabia.

BROOKS: Sure. So we have indeed downgraded our forecast for 2024 for Saudi Arabia to 1.7, which is a downward revision of 0.9. And this is entirely due to the impact of the production cuts, the mandatory production cuts from OPEC+ on oil output. But when we look at the non oil part of activity, that is actually still very robust. And although in the first quarter we did see some moderation in non oil activity as well.

Now going forward, we are expecting growth to pick up to 4.7 in 2025 as the impact of these production cuts wanes. And also, non-oil activity is very strong. Now, of course, risks to the outlook are very much linked to what happens with the production and price of oil. But I should also say that the country is also benefiting from some of the very large investment projects which are being rolled out, and that is having a positive impact on the Outlook.

DE HARO: Okay. And as I said, we have a question on Egypt from Fatima Ibrahim Amam. Sorry for my pronunciation. That goes as follows, could you please explain what are the reasons for lowering your projections for the Egyptian economy? And also what are your projections for inflation?

GOURINCHAS: I will turn to Petya again.

BROOKS: Sure. We have revised down a bit the forecast for Egypt both this year and next. We have 2.7 in fiscal year ‘24 and then 4.1 in ‘25. The downgrade for this year was very much related to the weaker than expected outturns that we saw in the first half of the year. But we are projecting a recovery. So growth next year is again expected to be 4.1. And that recovery is very much linked to the impact of the development, the expected development of the Ras Al-Hekma region, and also as the Red Sea disruptions abate. As well as the improvements in the functioning of the FX market.

Now, we have revised our inflation forecasts a little bit, and this is due to the passthrough of the depreciation as well as some adjustment in administrative prices. But that being said, we do expect inflation to come down gradually over time, and in 2025 we have it at a little bit over 20 percent on an average basis. Thank you.

DE HARO: Okay, we are going to be changing regions and I see Leticia from El Financiero. Please go ahead.

QUESTIONER: Thank you. Hello. Thank you for taking my questions. Have you detected inflationary pressures in Mexico due to the salary increase? Because this is one of the countries where the minimum salaries was grown the most. And also, I would like to know if the outlook for Mexico economy remains unchanged compared to the April WEO. Thank you.

DE HARO: We have another question on the outlook for the region, for Latin America as a whole. So first, maybe we can give a little bit of color on Latin America, and then we can go to Mexico.

GOURINCHAS: Okay. Well, I will ask Petya to come in on Latin America and Mexico.

BROOKS: Sure. Happy to do that. The outlook in the region is very much driven by, I would say, a lot of heterogeneity, a lot of differences across countries. And we have one set of countries which see a slowdown in growth this year and then a pickup next year, and Argentina definitely falls into that category. We also have a set of countries like Mexico and Brazil that saw very high growth last year, and then those growth rates moderating this year. But as a whole, the way I would characterize it is that the region has really weathered, as a whole, the Covid crisis and the shocks afterwards quite well. It’s been resilient, you know. So the — it was also among the first to respond to the inflationary pressures. So some of the slowing that we see observing is really as a result of the policies that are needed in order to replenish fiscal buffers as well as to fight inflation.

Now, when it comes to Mexico, we have revised down a bit the forecast for this year to 2.2. But this comes off from very strong growth last year of 3.2 percent, when we saw that last year we saw a lot of non-resident investment in construction and expansion in manufacturing activity, which was to a large extent also respond to the demand from the U.S. market. Now, as some of that is — is fading or is becoming less pronounced, and also reflecting the slowdown in the U.S. Those are the reasons, the main reasons behind the slight downward revision of our forecast for this year. Now, when it comes to inflation, it has stabilized since the middle of 2023. Although, as in other countries, we are seeing signs of stickier services inflation, and this is when some where some of the wage increases that you mentioned are playing a role. But altogether we see the stance of monetary policy as appropriate, and we do expect inflation to come back to target by the end of 2025.

DE HARO: Thank you, Petya. I see that there are other questions related to St. Kitts and Nevis. We will try to answer those bilaterally because we are running out of time, and we have only time for one more question. We are going to another soccer champions this time around. We’re going to Argentina. Liliana, please go ahead. Liliana, we cannot hear you. I think that you are muted.

QUESTIONER: Sorry. Good morning. Thank you. We are champions in fútbol, but also we are champions in inflation rates. So my first question will be what is your estimation for annual inflation for Argentina? And the second is what are the causes that explains the drop down of our GDP, annual GDP, that it was 2.7, if I remember, to -3.5 in the new forecast. Thank you.

GOURINCHAS: Yes. So on Argentina, let me say a few things and then pass it over to Petya. So first, inflation has been coming down. That’s the good news. Inflation has been coming down very significantly in Argentina. Now these are not the annual numbers, these are the year-on-year end year numbers. In 2023, it was around 211 percent, and in 2024, we’re projecting 140 percent, around 140 percent. That’s still a high number, but that also reflects a lot of the inflation that has already happened. And the sequential inflation is coming down quite fast on the back of very strong measures that have been implemented by the authorities in the country.

Now the key component of the measures that have been implemented is on the fiscal side. The fiscal side has always been an issue for many, many years in Argentina. And here, for the first time in a long, long time, the government has delivered a balanced budget. The question is whether it can continue doing so in the future. And that’s where engagement with the parliament and having high quality measures on the fiscal side is going to be very important. And there are signs that it’s moving in that direction.

Coupled with that is also a tightening of monetary policy, with an end to the monetary financing of the government. So all of these things are going in the direction of bringing inflation under control, which has been a key problem in the country, but it has an impact in terms of economic activity, of course, because there is less public spending, there is tighter monetary conditions. And this is, you know, this has led to a very significant slowdown for 2024 in Argentina, with an expected rebound in 2025 to around 5 percent.

Now, on the details of the revision, Petya can come in.

BROOKS: I don’t have much to add. Maybe just to say that a big part of that revision for this year, the downward revision of 0.7, is really the kind of the negative carryover from the very sizable contraction that we saw in the last quarter of last year. But looking ahead, even in the coming quarters of this year, we do expect growth to pick up and to rebound as we see the fading effects from the — from the fiscal tightening, as well as confidence returns and real wages, of course, go up.

DE HARO: Thank you, Petya. On behalf of Pierre-Olivier, Petya, and Jean-Marc, the Research Department, and also the Communications Department, we want to thank you all for attending this virtual press briefing. Please, if you have any questions, comments, feedback, send it to us, to IMF, to media@imf.org. I hope that you have a good rest of your day. Thank you very much.

Source – IMF