Source – ECA: Special Report 16/2021

About the report: During the 2014-2020 period, the Commission attributed over a quarter of the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP)’s budget to mitigate and adapt to climate change.

We examined whether the CAP supported climate mitigation practices able to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. We found that the €100 billion of CAP funds attributed to climate action had little impact on such emissions, which have not changed significantly since 2010. The CAP mostly finances measures with a low potential to mitigate climate change. The CAP does not seek to limit or reduce livestock (50 % of agriculture emissions) and supports farmers who cultivate drained peatlands (20 % of emissions).

We recommend that the Commission takes action so that the CAP reduces emissions from agriculture; takes steps to reduce emissions from cultivated drained organic soils; and reports regularly on the contribution of the CAP to climate mitigation.

ECA special report pursuant to Article 287(4), second subparagraph, TFEU.

This publication is available in 23 languages and in the following format:

Contents

- Executive summary

- Introduction

- Audit scope and approach

- Observations

- Conclusions and recommendations

- Acronyms and abbreviations

- Glossary

- Replies of the Commission

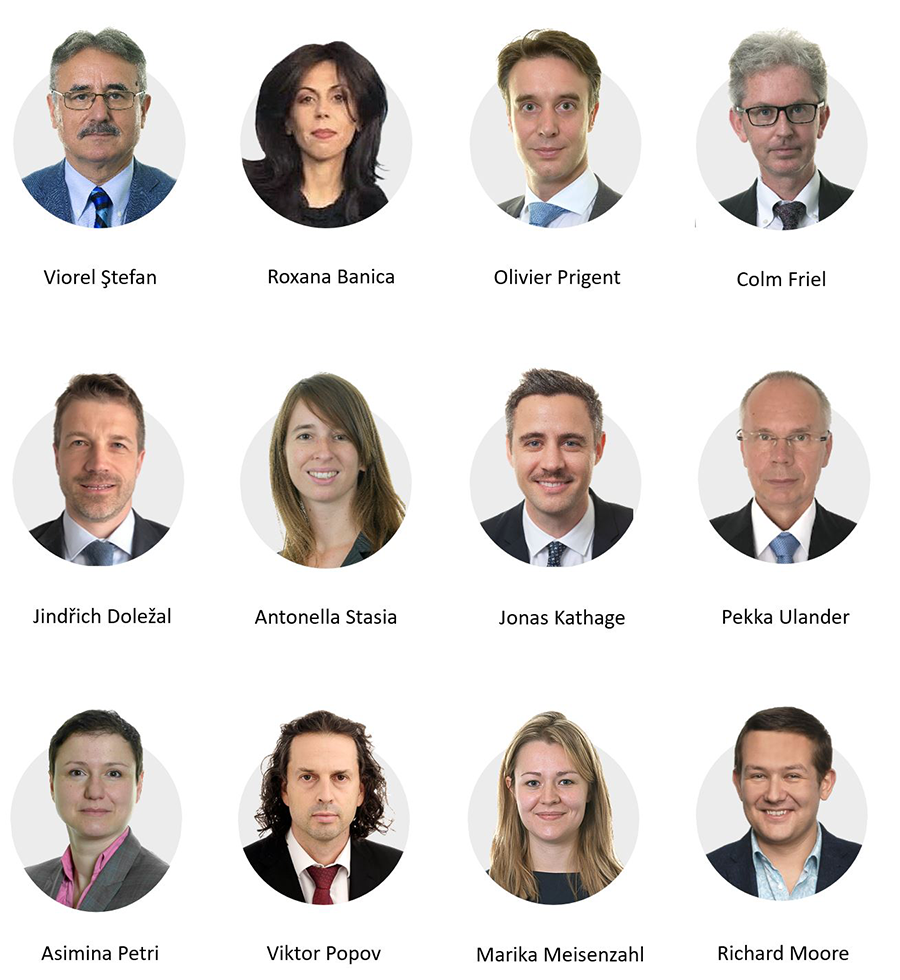

- Audit team

- Endnotes

- Timeline

- Contact

Executive summary

I

VIEmissions from chemical fertilisers and manure, accounting for almost a third of agricultural emissions, increased between 2010 and 2018. The CAP supports practices that may reduce the use of fertilisers, such as organic farming and grain legumes. However, we found that these practices have an unclear impact on greenhouse gas emissions. Instead, practices that are more effective received little funding.

VIIThe CAP supports farmers who cultivate drained peatlands, which emit 20 % of EU-27 agricultural greenhouse gases. Although available, rural development support was rarely used for their restoration. CAP rules also make some activities on the rewetted land ineligible for direct payments. The CAP did not increase support for afforestation, agroforestry and conversion of arable land to permanent grassland in 2014-2020 compared to 2007-2013.

VIIIDespite the increased climate ambition, cross-compliance rules and rural development measures changed little compared to the previous period. Therefore, these schemes did not incentivise farmers to adopt effective climate mitigation measures. While the greening scheme was supposed to enhance the environmental performance of the CAP, its impact on climate has been marginal.

IXWe recommend that the Commission should:

- take action so that the CAP reduces emissions from agriculture;

- take steps to reduce emissions from cultivated drained organic soils; and

- report regularly on the contribution of the CAP to climate mitigation.

Introduction

Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture

01Food production is responsible for 26 % of global greenhouse gas emissions1. Figure 1 shows that agriculture is responsible for most of these emissions. In its Farm to Fork strategy, the Commission, using IPCC guidelines that focus only on farm activities, wrote that in the EU (therefore ignoring the impact of imported animal foodstuff), ‘agriculture is responsible for 10.3 % of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions and nearly 70 % of those come from the animal sector’.

Source: ECA based on Poore, J. and Nemecek, T.: Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers, 2018.

Source: ECA based on Poore, J. and Nemecek, T.: Reducing food’s environmental impacts through producers and consumers, 2018.02Member States report greenhouse gases emitted on their territory using activity data linked to sources of emissions (e.g. animal types and numbers) with relevant emission factors. Figure 2 shows three main greenhouse gases which agriculture emits, their key sources in the EU as well as the proportion of these sources in total agriculture emissions, which represent 13 % of the total EU-27 greenhouse gas emissions (including an additional 2.7 % of land use emissions and removals from cropland and grassland). Additional emissions, not included in Figure 2, arise from the use of fuel for machinery and heating of buildings, representing around 2 % of the total EU-27 emissions.

Source: ECA based on the EU-27 greenhouse gas inventories in 2018 (EEA greenhouse gas data viewer, European Environment Agency (EEA)).

Source: ECA based on the EU-27 greenhouse gas inventories in 2018 (EEA greenhouse gas data viewer, European Environment Agency (EEA)).03Agriculture, and in particular livestock production, necessarily involves the emission of greenhouse gases. Some land use practices provide opportunities to reduce emissions or remove carbon dioxide (CO2) from the atmosphere by storing carbon in soil and in biomass (plants and trees). These practices include restoration of drained peatlands or afforestation.

04Figure 3 shows how greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture developed between 1990 and 2018. They decreased by 25 % between 1990 and 2010, mainly due to a decline in the use of fertilisers and in the number of livestock, with the largest fall between 1990 and 1994. Emissions have not declined further since 2010.

Source: ECA based on EU-27 greenhouse gas inventories 1990-2018 (EEA greenhouse gas data viewer).

Source: ECA based on EU-27 greenhouse gas inventories 1990-2018 (EEA greenhouse gas data viewer).Climate change policy in the EU

05The EU response to climate change is based on two strategies: mitigation and adaptation. Mitigation means reducing man-made greenhouse gas emissions or removing greenhouse gases from the atmosphere. Adaptation means adjusting to current or expected climate change and its effects. This report focuses on mitigation.

06In 1997, the EU signed the Kyoto Protocol. It thus committed to reducing its greenhouse gas emissions by 20 % by 2020, using 1990 emissions level as a baseline. In 2015, the EU became a party to the Paris Agreement. This increased the EU’s emissions reduction ambitions. The EU’s current policy framework aims to reduce the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions by 40 % by 2030. The Commission proposed to raise this target to 55 % and to achieve net zero emissions by 20502.

07The EU’s framework for climate change mitigation until 2020 had two main components, the emissions trading system and the effort-sharing legislation, which together accounted for 95 % of the EU greenhouse gas emissions in 2018 (Figure 4).

Source: ECA based on EEA Report No 13/2020, Trends and projections in Europe 2020.

Source: ECA based on EEA Report No 13/2020, Trends and projections in Europe 2020.08The EU has set reduction targets of 10 % by 20203 and 30 % by 20304 (compared to 2005) for emissions under the effort-sharing legislation. Figure 5 shows the 2020 targets set for each of the 27 Member States, which take account of income per capita. Each Member State decides how to meet its national target, and whether or not its agricultural sector will contribute.

Source: ECA based on Annex II of Decision No 406/2009/EC referred to in Footnote 3.

Source: ECA based on Annex II of Decision No 406/2009/EC referred to in Footnote 3.09According to the estimated 2019 greenhouse gas emissions under effort-sharing sectors, 14 out of 27 Member States had their 2019 emissions below the 2020 national targets5. For each Member State, we compared the emissions gap for the first period (2013-2020) with the emissions gap for the second period (2021-2030). For 2021, we used instead the latest estimate available for 2019. Figure 6 shows that the 2030 targets will be much more challenging for the EU.

Source: ECA based on the Commission’s EU climate action progress report from November 2020 (Table 6), the Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/2126 of 16 December 2020 and Regulation (EU) 2018/842 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018.

Source: ECA based on the Commission’s EU climate action progress report from November 2020 (Table 6), the Commission Implementing Decision (EU) 2020/2126 of 16 December 2020 and Regulation (EU) 2018/842 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 30 May 2018.10The Commission opted in 2011 to mainstream climate into the EU budget (“climate mainstreaming”). This involved integrating mitigation and adaptation measures (“climate action”) into EU policies and tracking the funds used on these measures with an objective of spending at least 20 % of the 2014-2020 EU budget on climate action6.

The role of the 2014-2020 CAP in climate action

11Currently, the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) has three broad objectives: viable food production, sustainable management of natural resources and balanced territorial development. Its management involves both the Commission and the Member States. Paying agencies in the Member States are responsible for administering aid applications, carrying out checks on applicants, making payments and monitoring the use of funding. The Commission sets much of the framework for spending, checks and monitors the work of paying agencies, and is accountable for the use of EU funds. The CAP has three blocks of support:

- direct payments to provide income support for farmers;

- market measures to deal with difficult market situations such as a sudden drop in prices; and

- rural development measures with national and regional programmes to address the specific needs and challenges facing rural areas.

12Since 2014, climate action7 is one of the nine specific objectives against which the Commission evaluates the performance of the Common Agricultural Policy. With climate mainstreaming, the Commission estimated that it would attribute €103.2 billion (€45.5 billion for direct payments and €57.7 billion for rural development measures) to climate change mitigation and adaptation in agriculture during the 2014-2020 period (Figure 7). This represents 26 % of the CAP budget and almost 50 % of total EU climate action spending8. The Commission’s reporting on climate expenditure does not differentiate between adaptation and mitigation.

Source: ECA based on Commission tracking of climate action.

Source: ECA based on Commission tracking of climate action.13Many measures that the Commission tracks as contributing to climate action primarily address biodiversity, water and air quality, and social and economic needs.

14In our special report 31/2016, we found that the Commission had overstated the CAP funds spent on climate action, and that 18 %, instead of the 26 % claimed by the Commission, would be a more prudent estimate. The difference came mainly from an overestimation of the impact of cross-compliance on climate mitigation; and from the fact that some of the coefficients assigned did not observe the conservativeness principle. The Commission recognised the possibility of some over- and under-estimation of climate relevance of certain spending with the current methodology but considered that its climate tracking approach to assess levels of climate spending in agriculture and rural development is sound.

15The Commission’s long-term target for the 2014-2020 CAP is to lower the greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture9. The Commission did not specify the decrease in emissions to be achieved.

The Commission’s strategy for intensifying climate mitigation efforts

16On 1 June 2018, the Commission presented legislative proposals on the 2021-2027 CAP. The Commission stated that the new CAP would “set the bar even higher” in increasing environmental and climate protection10. The Commission proposed a new performance-based model, giving Member States greater responsibility and accountability on the design of the CAP measures. Member States will describe them in their “CAP strategic plans”, which the Commission will have to approve.

17In December 2019, the Commission presented the European Green Deal providing a roadmap for making Europe the first climate-neutral continent by 2050. For the 2021-2027 period, the Commission proposed to spend 25 % of the EU budget on climate action but the Council increased it to 30 %11. Figure 8 shows strategies and legislative proposals issued by the Commission in 2020 on actions to achieve climate neutrality by 2050.

18In December 2020, the Commission issued recommendations to the Member States for the preparation of their proposed CAP strategic plans12. It recommended, for example, using eco-schemes for rewetting drained peatland, for promoting precision farming and conservation agriculture (with no or reduced ploughing). Our special report 18/2019 on EU greenhouse gas emissions recommended the Commission to ensure that the strategic plans for agriculture and land use contribute to achieving the 2050 reduction targets and to verify that Member States set out appropriate policies and measures for these sectors.

Source: ECA, based on Commission communications.

Source: ECA, based on Commission communications.Audit scope and approach

19We decided to carry out this audit because the Commission had attributed almost 26 % of the CAP budget (€103 billion) during the 2014-2020 period to climate action. Furthermore, climate was among the most important subjects of the political discussion on the future CAP and UN Sustainable Development Goal 13 requires taking action to combat climate change. We expect our findings to be useful in the context of the EU’s objective of becoming climate neutral by 2050.

20We examined whether the 2014-2020 CAP supported climate mitigation practices with a potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. We also examined whether the CAP better incentivised the uptake of effective mitigation practices in the 2014-2020 period than in the 2007-2013 period. We focused our work on the main sources of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture: livestock and manure storage, application of chemical fertilisers and manure, cultivation of organic soils and conversion of grassland and cropland.

21Our audit excluded climate mitigation projects funded under Horizon 2020 and LIFE. We also excluded from our scope fuel emissions in agriculture.

22We obtained our evidence from:

- a review of data on: EU-27 greenhouse gas emissions; livestock, cultivated crops and the use of fertilisers; rural development programmes and the Commission’s reports on direct payments;

- interviews with representatives of farmers, environmental and climate NGOs, and national authorities in Ireland, France and Finland, selected based on the proportion of their agricultural emissions, agricultural activities and approaches to climate change mitigation and carbon storage;

- a review of scientific studies assessing the effectiveness of mitigation practices and technologies;

- desk reviews of the agricultural greenhouse gas emissions of 27 Member States and the CAP actions taken to reduce them or to sequester carbon during the 2014-2020 period; and

- discussions with experts in agriculture and climate change to increase our knowledge and to comment on our emerging findings.

Observations

23We have split our observations into four sections. The first three sections assess the 2014-2020 CAP impact on the key sources of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture: livestock, application of chemical fertilisers and manure, and use of land. The last section deals with the design of the 2014-2020 CAP and its potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture.

The CAP has not reduced livestock emissions

24We examined whether there was an overall reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from feed digestion and manure storage over the period 2014-2020 CAP. We assessed the extent of CAP support for effective mitigation practices to reduce these emissions. We also examined whether some CAP aid schemes led to increases in greenhouse gas emissions.

25EU-27 greenhouse gas emissions from livestock have not decreased between 2010 and 2018. Feed digestion accounts for 78 % of livestock emissions while manure storage is responsible for the remaining 22 %. Emissions from beef and dairy cattle account for 77 % of livestock emissions (Figure 9).

Source: ECA based on the EU-27 greenhouse gas inventories.

Source: ECA based on the EU-27 greenhouse gas inventories.The CAP measures do not include a reduction of livestock

26For most Member States, livestock emissions are unchanged. Only Greece, Croatia and Lithuania showed significant emissions reductions between 2010 and 2018 (Figure 10). These reductions were mainly associated with large decreases (around 30 %) in dairy cow numbers rather than the results of CAP targeted mitigation policies. In these three countries, lack of competitiveness played the key role in the decline. Ireland, Hungary and Poland, on the other hand, have seen substantial emissions increases.

Source: ECA based on Member States’ greenhouse gas inventories.

Source: ECA based on Member States’ greenhouse gas inventories.27Reducing the livestock production would lower emissions from feed digestion and manure storage, but also from fertiliser used in feed production. Reducing overall livestock production in the EU would lower greenhouse gas emissions within the EU. The net impact would depend on changes to consumption of animal products. If this leads to higher imports, there would be a degree of ‘carbon leakage’13. However, the CAP does not seek to limit livestock numbers; nor does it provide incentives to reduce them. The CAP’s market measures include promotion of animal products, the consumption of which has not decreased since 2014 (Figure 11).

Source: ECA based on data from the Commission Prospects for Agricultural Markets in the EU 2020-2030, 2020.

Source: ECA based on data from the Commission Prospects for Agricultural Markets in the EU 2020-2030, 2020.28The above trends are based on supplies available to consumers so they also include food waste. As presented in our special report 34/2016, it is generally recognised that, at global level, around one-third of the food produced for human consumption is wasted or lost. Our report concluded that CAP has a role to play in combating food waste and recommended including this topic in the review of the CAP.

29In the Farm to Fork strategy, the Commission announced that it would review the EU promotion programme for agricultural products to promote sustainable production and consumption. The Commission published a Staff Working Document14 in which it evaluated the promotion policy on 22 December 2020. It continues to review the policy, with the intention of proposing legislative changes in 2022. The Farm to Fork strategy considered how the EU could, in the future, use its promotion programme to support the most sustainable, carbon-efficient methods of livestock production, as well as promote a shift to a more plant-based diet.

30In our review of studies, we found no effective and approved practices that can significantly reduce livestock emissions from feed digestion without reducing production (certain feed additives may be effective, but have not received regulatory approval). Many practices concerned with animal breeding, feeding, health and fertility management offer only a slow and marginal mitigation potential. Some of these practices encourage production expansion, and may thus increase net emissions (Box 1).

Box 1

The rebound effect and livestock emissions

Innovations in management practices and technology can increase the greenhouse gas efficiency of agricultural production. For example, advances in dairy cattle breeding have resulted in lower emissions per litre of milk produced, thanks to higher milk yield per animal. However, such efficiency gains do not translate directly into lower overall emissions. This is because technological change in the livestock sector has also lowered the production cost per litre of milk, leading to production expansion. This effect, known as the “rebound effect”, reduces the greenhouse gas savings from the technology that would occur without production expansion. The additional emissions caused by production expansion can be even larger than the savings achieved from greater efficiency, which means that the innovation causes overall emissions to increase15.

31We found four effective practices for reducing emissions from manure storage (acidification and cooling of manure, impermeable covers of manure stores, and biogas with manure as feedstock). Several Member States provided CAP support for these practices on a small number of farms (Table 1).

| Practice | Member States | Farms benefiting from the support |

| Slurry acidification | Denmark | 29 |

| Italy | 1 | |

| Poland | 2 | |

| Germany, France, Latvia, Lithuania | Unclear data | |

| Cooling of manure | Denmark | 30 |

| Estonia | 1 | |

| Poland | 2 | |

| Finland | 1 | |

| France, Italy, Austria, | Unclear data | |

| Impermeable covers | Belgium | 13 |

| Denmark | 503 | |

| Germany | 829 | |

| Estonia | 30 | |

| Spain | 344 | |

| Italy | 308 | |

| Luxembourg | 0 | |

| Hungary | 374 | |

| Malta | 16 | |

| Poland | 275 | |

| Slovenia | 45 | |

| Slovakia | 7 | |

| Finland | 30 | |

| Sweden | 5 | |

| France, Austria, Latvia, Lithuania Romania | Unclear data | |

| Production of biogas from manure | Belgium | 60 |

| Greece | 6 | |

| Spain | 0 | |

| France | 51 | |

| Croatia | 0 | |

| Italy | 20 | |

| Hungary | 129 | |

| Finland | 22 | |

| Sweden | 20 | |

| Lithuania, Poland, Romania | Unclear data |

Source: ECA based on data provided by Member States.

Several CAP measures maintain or increase greenhouse gas emissions driven by livestock

32On average, specialist cattle farmers depend on direct payments for at least 50 %16 of their income. This level of dependency is higher than for arable farmers.

33All Member States except Germany provide a part of their direct payments (mostly between 7 % and 15 %)17 in the form of voluntary coupled support (VCS), 74 % of which supports livestock farming (Figure 12). VCS encourages the maintenance of livestock numbers because farmers would receive less money if they reduced livestock numbers. At EU level, VCS accounts for 10 % of direct payments (€4.2 billion per year)18.

Source: ECA based on the Commission document: Voluntary Coupled Support, 2020, p.3.

Source: ECA based on the Commission document: Voluntary Coupled Support, 2020, p.3.34A 2020 study19 estimated that EU’s greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture (without land use emissions) would fall by 0.5 % if the VCS budget for cattle, sheep and goats were reallocated to basic payments for agricultural land. A 2017 study20 found that without direct payments, agriculture emissions would be 2.5 % lower, with 84 % of the decrease coming from a reduction in beef and dairy production and the associated lower use of fertiliser on pastures. A Commission study from 201721 estimates that agriculture emissions would decrease by 4.2 % if direct payments ceased, and by 5.8 % if rural development support were abolished as well. This study estimates that about 7 % of the agricultural area would become available for land-based mitigation measures such as afforestation. These reductions do not take into account the possible leakage effect (see paragraph 27), which these three studies estimate between 48 % and almost 100 % (in the absence of trade barriers).

35A 2020 study22 found that emissions in the EU would fall by 21 % if roughly half of direct payments were paid to farmers in return for greenhouse gas emissions reduction. Two thirds of the reduction would come from changes in production, with beef, sheep and goat meat and fodder production declining the most. One third of the reduction would come from the uptake of mitigation practices, among which technologies in the dairy sector, biogas in the pig sector and the fallowing of peatlands. These benefits would be offset by increased emissions elsewhere by about 4 % of current EU agricultural emissions, providing a net reduction of 17 %.

36Additional emissions stem from deforestation associated with feed production, especially soybeans23. If imports are taken into account, the proportion of emissions attributable to the production of animal products consumed in the EU increases further (compared to looking at emissions caused directly by agriculture within the EU). When imports are included, animal products represent an estimated 82 % of the carbon footprint (Figure 13) but only 25 % of calories of the average EU diet24.

Source: Sandström, V. et al.: The role of trade in the greenhouse gas footprints of EU diets, 2018, p. 55 (constructed with data received from V. Sandström).

Source: Sandström, V. et al.: The role of trade in the greenhouse gas footprints of EU diets, 2018, p. 55 (constructed with data received from V. Sandström).Emissions from fertiliser and manure on soils are increasing

37We assessed whether measures under the 2014-2020 CAP reduced greenhouse gas emissions from the application of chemical fertiliser and manure.

38The application of chemical fertiliser and livestock manure, together with depositions by grazing animals, accounts for the majority of greenhouse gas emissions from nutrients in soils. Between 2010 and 2018, emissions from nutrients in soils increased by 5 %. This increase is primarily due to an increase in fertiliser use, while the other main source of emissions, livestock manure, has been more stable (Figure 14).

Source: ECA based on the EU-27 greenhouse gas inventories.

Source: ECA based on the EU-27 greenhouse gas inventories.39Between 2010 and 2018, emissions from chemical fertiliser and livestock manure increased in eight Member States (Figure 15). The increase was largest (exceeding 30 %) in Bulgaria, Czechia, Hungary, Romania and Slovakia. Only in Greece and Cyprus did emissions clearly decline. These trends at country level are almost all driven by changes in chemical fertiliser use. The group of Member States showing no change or no significant change include those with highest greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture per hectare of utilised agricultural area25.

Source: ECA based on Member States’ greenhouse gas inventories.

Source: ECA based on Member States’ greenhouse gas inventories.Derogations from the Nitrates Directive partly offset its positive impact on emissions from manure application

40As the subsidies have not been linked to any reduction in livestock production (paragraphs 26–34), the quantities of the manure have not decreased (Figure 14). The maintained level of livestock production also keeps fertiliser use high, as more nitrogen is required for animal products than for plant-based foods26.

41Under the CAP, farmers are subject to “cross-compliance” rules (paragraph 77). Statutory management requirement (SMR) 1 – “Protection of waters against pollution caused by nitrates from agricultural sources” covers compliance with the Nitrate Directives27, which applies to all farmers, irrespective of whether they receive CAP support. The Nitrate Directive requires balanced use of fertilisers, establishes limits in the amount of applied manure, and defines periods when their application is prohibited. A 2011 study conducted for the Commission28 found that, without the Nitrates Directive, total N2O emissions across the EU in 2008 would have been 6.3 % higher, mainly due to the increase in total nitrogen leaching in ground and surface waters.

42As of 2020, four countries (Belgium, Denmark, Ireland, and the Netherlands) obtained a derogation from the Nitrates Directive on the limit of applied manure. These four countries are among the highest greenhouse gas emitters per hectare of utilised agricultural area29. Derogations may include conditions that could counterbalance the negative impact of spreading more manure onto soil than is normally allowed. The 2011 study estimated that derogations increase gaseous nitrogen emissions by up to 5 %, with an increase of up to 2 % in N2O.

43We analysed the information provided by the Irish authorities on derogations under the Nitrates Directive (Figure 16). Since 2014, in Ireland, the area under derogation has increased by 34 % and the number of animals in farms with derogations grew by 38 %. In the same period, emissions from chemical fertilisers increased by 20 %, emissions from manure applied to soils by 6 % and indirect emissions from leaching and run-off by 12 %.

Source: ECA based on Nitrates Derogation Review 2019: report of the Nitrates Expert Group, July 2019, p. 12.

Source: ECA based on Nitrates Derogation Review 2019: report of the Nitrates Expert Group, July 2019, p. 12.44In our review of studies, we found no effective practices for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from manure application, other than reducing the amount applied. The CAP supports practices that apply manure near or into the soil (e.g. trailing hose/shoe). Such practices can be effective for reducing ammonia emissions, but they are not effective for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and may even increase them30.

The CAP did not reduce the use of chemical fertilisers

45The CAP supports a number of farming practices intended to reduce fertiliser use. In the following paragraphs, we discuss five farming practices and associated CAP support during 2014-2019 (see Table 2 and paragraphs 46–51 for individual assessments of the practices):

- two practices which have received considerable CAP support but their effectiveness to mitigate climate change is unclear according to our review of studies (organic farming and grain legumes), and

- three practices which we identified as being effective for climate change mitigation, but which have received minimal CAP support (forage legumes, variable rate nitrogen technology and nitrification inhibitors).

| Practice/technology | CAP impact on uptake | Effectiveness for climate mitigation |

| Organic farming | Moderate | Unclear |

| Grain legumes (arable) | Moderate | Unclear |

| Forage legumes (grassland) | None-minimal | Effective |

| Variable rate nitrogen technology | None-minimal | Effective |

| Nitrification inhibitors | None-minimal | Effective |

Source: ECA based on data provided by Member States for 2019.

The CAP encouraged organic farming and cultivation of grain legumes but the impact on the use of fertilisers is unclear

46Organic farming does not allow the use of chemical fertilisers. However, the conversion of conventional to organic farming does not necessarily lead to reduced greenhouse gas emissions. There are two main conversion scenarios, both putting in doubt whether the expansion has reduced greenhouse gas emissions:

- If a conventional farmer with low fertiliser use (such as upland grazing) converts to organic farming, the impact on emissions will be low.

- If a farmer with higher fertiliser use converts to organic farming, the farm’s emissions will be significantly reduced. However, lower yields on organic farms may induce other farms to use additional fertiliser or land to produce – and emit – more31 (Figure 17).

Source: ECA based on World Resources Institute: Regenerative Agriculture: Good for Soil Health, but Limited Potential to Mitigate Climate Change.

Source: ECA based on World Resources Institute: Regenerative Agriculture: Good for Soil Health, but Limited Potential to Mitigate Climate Change.47The CAP, through rural development aid, contributed to an expansion of organic farming from 5.9 % of EU farmland in 2012 to 8.5 % in 2019. However, we could not find reliable evidence regarding the impact of this expansion on fertiliser and manure use or greenhouse gas emissions.

48Grain legumes have lower nitrogen fertilisation requirements than other crops because they have the ability to biologically “fix” nitrogen from the air. All Member States except Denmark offered CAP support for grain legumes, whether under greening, VCS, or rural development aid. According to Eurostat, the area of land used for grain legumes rose between 2010 and 2018 from 2.8 % to 3.8 % of total EU farmland. Promoting grain legumes involves similar trade-offs as promoting organic farming: if legumes replace crops that receive little fertiliser, they will not affect fertiliser use to any great extent. If they replace crops that receive more fertiliser, they risk shifting emissions to other farms (Figure 17). Data at farm level on the impact of the CAP supported cultivation of grain legumes on the use of fertilisers is not available.

The CAP provides low support for effective mitigation practices

49Forage legumes, such as clover and alfalfa, can be used in grassland and lower fertiliser use due to their ability to fix nitrogen from the air. In contrast with grain legumes, forage legumes fix larger amounts of nitrogen and do not lower grassland yield, avoiding the risk of shifting emissions to other farms. According to information provided by the Member States, we estimate maximum coverage of this practice to be 0.5 % of EU farmland.

50Variable-rate nitrogen technology is a particular type of precision farming that matches fertiliser applications to crop needs within the same field. According to the JRC32, this technology can lead to reductions in fertiliser use of around 8 %, without reducing yields33. According to the information provided by the Member States, nine of them (Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Spain, Italy, Latvia, Poland, Slovakia and Sweden) used CAP support for this practice in the 2015-2019 period, on 0.01 % of EU farms.

51Nitrification inhibitors are compounds that slow down the conversion of ammonium to nitrate, which reduces N2O emissions. They can be an effective mitigation technology, with estimated direct N2O emission decreases of around 40 % without affecting yield. They are particularly effective when used together with urease inhibitors34. However, we found in our audit that the use of nitrification inhibitors has not received support from the CAP.

The CAP measures did not lead to an overall increase in carbon content stored in soils and plants

52We examined whether the 2014-2020 CAP measures supported a reduction in emissions from land use or an increase in the carbon sequestration on grassland and cropland. We assessed whether the CAP supported mitigation practices having the potential to materially contribute to climate mitigation, and whether it increased their uptake.

53Since 2010, net emissions from cropland and grassland have ceased to decline. Emissions in seven Member States were stable or fluctuating without clear trends, while they increased in twelve countries and decreased in another eight countries (Figure 18).

Source: ECA based on Member States’ greenhouse gas inventories.

Source: ECA based on Member States’ greenhouse gas inventories.54Emissions from land use depend on the soil type. Organic soils are particularly rich in organic matter and are identified according to specific parameters35. All other types of soils are considered mineral soils. Figure 19 shows that cultivated organic soils are the main source of emissions from land use. Emissions from organic soils have been rather stable, down by 1 % in 2018 from the 2010 level. Removals from cropland and grassland on mineral soils have decreased, since 2010, by more than 8 %.

Source: ECA based on Member States’ greenhouse gas inventories.

Source: ECA based on Member States’ greenhouse gas inventories.Almost half of the Member States aim to protect untouched peatland

55Peatlands are a type of wetland with a thick layer of organic soil, particularly rich in organic matter. In the EU-27, they cover around 24 million hectares36 and store about 20-25 % of the total carbon in EU soils (on average 63 billion tonnes CO2eq)37. When untouched, they act as a carbon sink. However, when drained, they become a source of greenhouse gas emissions. In the EU-27, over 4 million hectares of drained organic soils, including peatland, are managed as cropland or grassland. This represents about 2 % of the total cropland and grassland area in the EU, but it accounts for 20 % of EU-27 agriculture emissions. Germany, Poland and Romania are the largest CO2 emitters from drained organic soils in the EU (Figure 20).

Source: ECA based on Greifswald Mire Centre (from EU inventories 2017, submission 2019).

Source: ECA based on Greifswald Mire Centre (from EU inventories 2017, submission 2019).56Figure 21 further illustrates how much carbon is annually estimated to be lost, i.e. released into the atmosphere, from organic soils. It shows also that mineral soils annually store additional carbon, mainly due to grassland, by removing it from the atmosphere. However, this mitigation effect is more than offset by emissions from cultivated organic soils. The potential of restoring peatlands is also acknowledged in a study that found that rewetting just 3 % of EU agricultural land would reduce agricultural greenhouse gas emissions by up to 25 %38.

Source: ECA, based on 2020 United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change EU inventories.

Source: ECA, based on 2020 United Nations Framework Convention for Climate Change EU inventories.57The 2014-2020 CAP does not contain an EU-wide measure to prevent untouched peatlands from conversion to agricultural land. The Commission proposed a good agricultural and environmental condition (GAEC) on the protection of wetlands and peatlands under the 2021-2027 CAP.

58Twelve Member States informed us that in the 2014-2020 period they promoted peatland conservation through the CAP. The area where a ban on drainage applies (about 600 000 ha) corresponds to 2 % of the EU’s overall peatland area. Seven of these Member States (Estonia, Italy, Ireland, Lithuania, Hungary, Poland and Slovenia) activated rural development support to protect such areas. The remaining five countries (Belgium, Czechia, Germany, Denmark and Luxembourg) protected peatland with cross-compliance or greening requirements.

59In the 2014-2020 period, six Member States (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Italy, Hungary, and Sweden) informed us that they activated measures under rural development to support restoration of drained peatland. Those countries supported such restoration on 2 500 hectares, while in Germany 113 beneficiaries participated in a similar scheme. The Commission does not have information on the areas of peatland restored.

60Instead of ensuring the full protection and conservation of peatland, the current CAP allows farmers that cultivate drained organic soils to receive direct payments for such areas, despite their negative impact on climate. In addition, if restoration means no agricultural activity is performed, the area may not be eligible for direct payments. This would make restoration unattractive to farmers.

The CAP offers limited protection of the carbon stored in grassland

61According to the EU greenhouse gas inventories for 2018, grassland on mineral soils removed 35 million tonnes CO2eq from the atmosphere. Most of this contribution comes from land converted to grassland in the last 20 years. In addition, grassland stores more carbon in the soil than cropland because the grass roots take up more carbon and the soil is less disturbed. If grassland is converted to arable land, this accumulated carbon is released back into the atmosphere. Some of the accumulated carbon may also be released if grassland is periodically ploughed to restore its productivity. Preventing both the conversion of grassland into cropland and frequent ploughing can therefore avoid greenhouse gas emissions.

62Extensively grazed grassland can sequestrate carbon. Thus, carbon sequestration in pasture land can mitigate to a variable extent the emissions of the livestock it feeds. The 2007-2013 CAP included measures for maintaining permanent grassland under the cross-compliance rules. The greening scheme, introduced in 2015, included two requirements for protecting permanent grassland (Figure 25) with the main objective of preserving carbon stock39.

63The first requirement asks Member States to maintain a ratio of permanent grassland on the total area declared for direct payments based on a reference period. A study from 2017 pointed out that the CAP protected a larger area of permanent grassland before 201540. Additionally, the Commission’s figures from 2019 indicate that in 21 countries and regions, the permanent grassland ratio decreased; in two cases (the Sachsen-Anhalt region in Germany, and Estonia), this decrease exceeded the permitted 5 % margin and the Member States had to take corrective actions.

64Decreases in permanent grassland area, mainly by conversion of permanent grassland to arable land, lead to greenhouse gas emissions. In addition, we reported in 202041 that ploughing and reseeding of permanent grassland, which emits greenhouse gases (both CO2 and N2O)42, also occurred in practice (39 % of farmers interviewed).

65As the greening requirement concerning the permanent ratio bans neither the conversion of permanent grassland to other uses nor ploughing and reseeding of permanent grassland, the effectiveness of this requirement to protect carbon stored in grasslands is significantly reduced.

66The second requirement introduced the concept of “environmentally sensitive permanent grassland” (ESPG) to protect the most environmentally sensitive areas within Natura 2000 areas from both conversion to other uses and ploughing. Member States had the option to designate additional areas outside of the Natura 2000 network, for example grassland on organic soils.

67Eight Member States decided to designate all their Natura 2000 areas as environmentally sensitive, while others designated specific land types within Natura 2000 areas (Figure 22). Overall, 8.2 million hectares of permanent grassland were designated as environmentally sensitive43, which represents 52 % of Natura 2000 grassland area and 16 % of EU permanent grassland. Four Member States decided to protect 291 thousand hectares of permanent grassland outside of Natura 2000 sites (representing an additional 0.6 % of the EU permanent grassland).

Source: ECA, based on European Commission, Direct payments 2015-2020 Decisions taken by Member States: State of play as from December 2018, 2019.

Source: ECA, based on European Commission, Direct payments 2015-2020 Decisions taken by Member States: State of play as from December 2018, 2019.68The greening requirement concerning ESPG can better protect the carbon stored in grasslands than the permanent grassland ratio requirement, as under ESPG both conversion of grassland to other uses and ploughing is banned.

No major uptake of effective mitigation measures on arable land

69The amount of carbon stored in and emitted or removed from cropland depends on crop type, management practices, and soil and climate variables. For example, perennial woody vegetation in orchards, vineyards, and agroforestry systems can store carbon in long-lived biomass.

70In scientific studies, we identified four effective measures for arable land on mineral soils that can help to remove greenhouse gas emissions: the use of catch/cover crops, afforestation, agroforestry, and the conversion of arable land to permanent grassland.

71Cover/catch crops are grown to reduce the period during which soil is left bare, in order to limit the risk of soil erosion. A further impact of catch/cover crops is an increase in soil carbon storage. This impact is higher if the vegetation cover is dense, roots are deep and crop biomass is incorporated into the soil. According to Eurostat data for the EU-27, such crops covered 5.3 million hectares in 2010 and 7.4 million hectares in 2016 (7.5 % of the EU’s arable land). Even if the increase by 39 % had been due to the 2014-2020 CAP, its maximum impact on greenhouse gas emissions would represent a reduction of annual emissions from agriculture (including cropland and grassland) by 0.6 %.

72The versions of the cross-compliance rules in force in 2007-2013 and in 2014-2020 both contained a requirement for minimum soil cover (GAEC 4) which requires cover crops to be grown on parcels at risk of soil erosion. While the general provisions for cross-compliance are set at EU level, it is up to Member States to define national standards. Consequently, some Member States imposed stricter requirements than others. In Czechia, for example, the condition was extended to arable land parcels with an average slope exceeding 4 degrees, while in the 2007-2013 period it was applied to land with a slope of more than 7 degrees. The Commission does not have uptake data for GAEC 4 at EU level that would allow comparison of the possible impact of this rule before and after 201544.

73In addition to GAEC 4, farmers could cultivate catch/cover crops to meet the ecological focus area requirement under the greening scheme (Figure 25). Twenty Member States used this possibility. According to an evaluation study from 201745, catch crops were the second most common option used by farmers to meet their ecological focus area obligations; in 2016, they declared such crops on 2.92 million hectares. In most Member States, however, farmers grew most of the declared catch crops before the introduction of the greening scheme. This means that the greening scheme had a negligible impact on the size of areas cultivated with catch/cover crops and on climate mitigation; this was confirmed by the conclusions of the evaluation study.

74Afforestation of marginal arable land can be an effective climate mitigation measure, which stores carbon in soil and trees. Agroforestry is less effective as the density of trees, bushes or hedges is lower but its advantage is that agricultural production can still take place on the land. Both mitigation practices have been traditionally supported with rural development funds. Figure 23 shows that their uptake was low compared to the original targets, that it was lower during 2014-2020 compared to 2007-2013 and that, consequently, the estimated overall impact of these rather effective climate mitigation measures on greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture is low.

Source: ECA based on data from the Commission’s Evaluation study of the forestry measures under Rural Development 2019 and from the 2019 Annual Implementation Reports of Rural Development Programmes. The values on the mitigation impact are taken from a 2016 Ricardo-AEA study.

Source: ECA based on data from the Commission’s Evaluation study of the forestry measures under Rural Development 2019 and from the 2019 Annual Implementation Reports of Rural Development Programmes. The values on the mitigation impact are taken from a 2016 Ricardo-AEA study.75Member States usually support the conversion of arable land to permanent grassland through their agri-environment-climate schemes under the rural development support. We have no data on the total area of arable land converted to permanent grassland in 2017-2013. During 2014-2019, eleven Member States supported such practices (Belgium, Bulgaria, Czechia, Germany, Estonia, Spain, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Hungary and Romania) and, by 2019, had converted an area of 517 000 hectares of arable land to permanent grassland. We estimate that the conversion of arable land to permanent grassland could remove up to 0.8 % of annual emissions from agriculture, until soils reach a new equilibrium state in which carbon releases and removals are equal (estimated by the IPCC at around 20 years).

The 2014-2020 changes to the CAP did not reflect its new climate ambition

76We assessed whether the 2014-2020 CAP framework was designed to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture. We examined how targets had been set for CAP-funded climate mitigation actions, and whether the 2014-2020 CAP schemes had significantly greater climate mitigation potential than the schemes used in the 2007-2013 period. We also examined the data that the Commission uses to monitor the impact of climate action and whether the polluter-pays principle applies to greenhouse gas emitters in agriculture.

Few new incentives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture

77While climate became a specific CAP objective from 2014, the Commission did not set a specific target in terms of emission reduction to be achieved with the €100 billion reported on climate action during the 2014-2020 period. Member States were not required to set their own climate mitigation targets to be achieved with 2014-2020 CAP funds, and did not do so. The only targets that Member States reported to the Commission were those for rural development support, indicating how much funds they intend to spend on climate action, and how much agricultural or forest area or livestock will be covered with this expenditure.

78Cross-compliance makes a link between CAP payments and a set of basic standards to ensure the good agricultural and environmental condition of land (GAECs) and certain obligations, known as statutory management requirements (SMRs). SMRs are defined in EU legislation on the environment, climate change, public, animal and plant health, and animal welfare.

79Paying agencies, which administer CAP payments in Member States, check the adherence of cross-compliance rules for a minimum of 1 % of farmers. If a farmer has breached some of them, depending on the extent, severity and permanence of the infringement, paying agencies may reduce the aid by between 1 % and 5 %, unless the infringement is minor and the farmer can remedy the situation. Farmers with repeated breaches can have their payments reduced up to 15 %, and by greater amounts where breaches were intentional.

80In our our special report 26/2016, we highlighted significant variations between Member States in the application of penalties for breaches of cross-compliance rules. The European Commission’s Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development’s (DG AGRI) Annual Activity Report46 shows that 2.5 % of all EU farmers were inspected for the 2018 claim year, and that one in four of the inspected farmers had aid reduced for breaches of at least one of the cross-compliance rules.

81Cross-compliance rules relevant for climate mitigation did not change much between the 2007-2013 and 2014-2020 periods; therefore, their potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions in 2014-2020 did not significantly increase. The Commission does not have uptake data for mitigation practices used by farmers because of the cross-compliance rules. Without this data, it is not possible to estimate the impact of cross-compliance rules on greenhouse gas emissions47.

82Furthermore, our special report 4/2020 on the use of new technologies for CAP monitoring highlighted that paying agencies regularly detect breaches of cross-compliance rules benefiting climate (Figure 24). That audit found that paying agencies had not started using the Copernicus Sentinel data, which allows to monitor all farmers rather than just a sample of them; using such data could increase farmers’ adherence to these rules.

Source: ECA based on Commission statistics on the Member States’ results of their cross-compliance inspections for 2015-2017.

Source: ECA based on Commission statistics on the Member States’ results of their cross-compliance inspections for 2015-2017.83Compared to the 2007-2013 period, the major change in the design of direct payments to farmers in the 2014-2020 period was a greening payment scheme (Figure 25), introduced in 2015. Its objective was to enhance environmental performance of the CAP by supporting agricultural practices beneficial for the climate and the environment48. Nevertheless, the potential of the greening payment scheme to contribute to climate mitigation was reduced from the outset, as its requirements were not aimed at reducing livestock emissions, which are responsible for half of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture.

Source: ECA.

Source: ECA.84While crop diversification has limited potential to benefit climate, the permanent grassland and ecological focus areas requirements could have contributed to climate mitigation by storing carbon in plants and soils49. However, a model-based study from 201750 showed that these components triggered few changes in farming practices: the permanent grassland and ecological focus areas requirements affected 1.5 % and 2.4 % of farmland respectively (see also our special report 21/2017).

85The farmers could meet the ecological focus areas requirement with practices or elements present on the farm before the introduction of greening. So only a small proportion of farmers was required to introduce new mitigation practices that they did not use before 2015. We also found that the effectiveness of the grassland requirement to protect carbon stored in grasslands is limited (paragraphs 61–68). We consider that greening, as currently designed, will not significantly contribute to climate mitigation. A 2017 evaluation study for DG AGRI concluded that the various greening scheme elements have either uncertain or positive but minimal impact on climate mitigation51.

86In the 2014-2020 period, 3.2 % of the rural development funds aimed primarily at reducing greenhouse gas emissions or promoting carbon sequestration. Measures targeting primarily other objectives, for example biodiversity, could also contribute to climate mitigation. However, the 2014-2020 rural development programmes did not offer many new climate mitigation measures in addition to those available during the 2007-2013 period or their uptake was low (paragraphs 58–59).

87The Commission’s common monitoring and evaluation framework collects data on climate mitigation for each Member State, such as the greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, share of land under contracts targeting climate change or share of livestock targeted for emission reduction. However, the monitoring framework does not provide information on the types of funded climate mitigation practices (e.g. precision farming), their uptake and estimated impact on greenhouse gas emissions. The ad-hoc evaluations contracted by the Commission were also hampered by a lack of reliable data, and did not allow the impact of CAP measures on climate change to be assessed52. We do not consider that the proposed post-2020 indicators will improve the situation, as pointed out in our opinion 7/201853 concerning the Commission’s post-2020 CAP proposals.

88Rural development annual implementation reports should contain information on the impact of climate mitigation measures funded with rural development support. The Commission reported that 30 out of 115 authorities managing rural development support provided information in 2019 on the net contribution of measures funded with rural development support to greenhouse gas emissions54. Managing authorities used various approaches to calculate the impact of the funded measures on greenhouse gas emissions, so it is not possible to sum the individual figures.

The EU does not apply a polluter-pays principle for agricultural emissions

89According to the polluter-pays principle55, those who cause pollution should meet the costs to which it gives rise. For climate, the principle can be implemented through bans or limits on greenhouse gas emissions, or by carbon pricing (for example, by means of a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade system). Our special report 12/2021 assesses whether this principle is well applied in several environmental policy areas, including water pollution from agriculture.

90EU law explicitly applies the polluter-pays principle to its environmental policies, but not to agricultural greenhouse gas emissions56. Agriculture neither falls under the EU Emissions Trading System, nor is subject to a carbon tax. The Effort-Sharing Decision puts no direct limits on greenhouse gas emissions from EU agriculture. The CAP also does not prescribe any emission limits.

Conclusions and recommendations

91The Commission attributed over €100 billion of CAP funds during the 2014-2020 period to tackling climate change. Member States can decide on reductions of greenhouse gas emissions to be achieved in the agricultural sector. However, these emissions have changed little since 2010 (paragraphs 01–18). In this audit, we examined whether the 2014-2020 CAP supported climate mitigation practices with a potential to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from three key sources: livestock, chemical fertilisers and manure, and land use (cropland and grassland). We also examined whether the CAP better incentivised the uptake of effective mitigation practices in the 2014-2020 period than in the 2007-2013 period (paragraphs 19–22).

92Livestock emissions, accounting for half of greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, including land use emissions and removals from cropland and grassland, did not decrease between 2010 and 2018. These emissions are directly linked to the size of the livestock herd, and cattle cause two thirds of them. There are no clearly effective measures to reduce emissions from feed digestion. We identified four potentially effective mitigation measures for emissions from manure management, but the CAP rarely incentivised their uptake. However, the CAP does not seek to limit livestock numbers; nor does it provide incentives to reduce them. The CAP market measures include promotion of animal products, the consumption of which has not decreased since 2014. This contributes to maintaining greenhouse gas emissions rather than reducing them (paragraphs 24–36).

93Greenhouse gas emissions from the use of chemical fertilisers and manure, which account for one third of the EU emissions from agriculture, increased between 2010 and 2018. The CAP has supported an expansion of organic farming and grain legumes, but the impact of such practices on greenhouse gas emissions is unclear. The CAP has provided little or no support to effective mitigation practices such as nitrification inhibitors or variable rate nitrogen technology (paragraphs 37–51).

Recommendation 1 – Take action so that the CAP reduces emissions from agricultureThe Commission should:

- invite the Member States to establish a target for reducing greenhouse gas emissions from their agricultural sector;

- assess Member States’ CAP strategic plans in view of limiting the risk that CAP schemes increase or maintain greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture; and

- ensure the CAP provides effective incentives to reduce greenhouse gas emissions from livestock and fertilisers that contribute to achieving EU climate goals.

Timeframe: December 2023

94Cultivated drained organic soils represent less than 2 % of EU farmland, but are responsible for 20 % of EU-27 agriculture emissions. Cultivated drained organic soils are eligible for direct payments while restored peatlands/wetlands might not always be eligible. While some Member States offered support for restoration of drained peatlands, its uptake was too low to have an impact on the emissions from organic soils, which have been stable since 2010. The 2014-2020 CAP has not increased its support of carbon sequestration measures such as afforestation and the conversion of arable land to grassland compared to the 2007-2013 period. While there has been an increase in areas covered with catch/cover crops between 2010 and 2016, the estimated impact on climate mitigation is low (paragraphs 52–75).

Recommendation 2 – Take steps to reduce emissions from cultivated drained organic soilsThe Commission should:

- introduce a monitoring system to support the assessment of the impact of the post-2020 CAP on peatland and wetland; and

- incentivise the rewetting/restoration of drained organic soils, for example through direct payments, conditionality, rural development interventions or other carbon farming approaches.

Timeframe: September 2024

95The Commission reported 26 % of CAP funding as benefiting climate action, but did not set a specific mitigation target for these funds. The Commission’s monitoring system does not provide data that would allow a proper monitoring of the impact of CAP climate funding on greenhouse gas emissions. While the greening scheme was supposed to enhance the environmental and climate impact of direct payments, its climate benefits have been marginal. As neither cross-compliance rules nor rural development measures have changed significantly compared to the 2007-2013 period, they did not encourage farmers to adopt new effective climate mitigation practices. EU law does not apply a polluter-pays principle to greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture (paragraphs 76–90).

Recommendation 3 – Report regularly on the CAP’s contribution to climate mitigationIn line with the EU’s increased climate ambition for 2030, the Commission should:

- set monitoring indicators that allow an annual assessment of the effect of the 2021-2027 CAP funded climate mitigation measures on net greenhouse gas emissions and report them regularly; and

- assess the potential to apply the polluter-pays principle to emissions from agricultural activities, and reward farmers for long-term carbon removals.

Timeframe: December 2023

This Report was adopted by Chamber I, headed by Mr Samo Jereb, Member of the Court of Auditors, in Luxembourg on 7 June 2021.

For the Court of Auditors

Klaus-Heiner Lehne

President

Acronyms and abbreviations

CAP: Common Agricultural Policy

CH4: Methane

CO2: Carbon dioxide

DG AGRI: European Commission’s Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development

EEA: European Environment Agency

ESPG: Environmentally sensitive permanent grassland

ETS: Emissions trading scheme

GAEC: Good agricultural and environmental conditions

IPCC: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change

N2O: Nitrous oxide

SMR: Statutory management requirement

VCS: Voluntary coupled support

Glossary

Agri-environment-climate measure: Any one of a set of optional practices going beyond the usual environmental requirements and entitling farmers to payment from the EU budget.

Carbon leakage: Increase in GHG emissions in one country/region (e.g. outside the EU) as a result of climate change mitigation measures to limit such emissions in another country/region (e.g. an EU Member State).

Common Agricultural Policy: The EU’s single unified policy on agriculture, comprising subsidies and a range of other measures to guarantee food security, ensure a fair standard of living for the EU’s farmers, promote rural development and protect the environment.

CO2 eq.: CO2 equivalent, a comparable measure of the impact of greenhouse gas emissions on the climate, expressed as the volume of carbon dioxide alone that would produce the same impact.

Cross-compliance: A mechanism whereby payments to farmers are dependent on their meeting requirements on the environment, food safety, animal health and welfare, and land management.

Direct payment: An agricultural support payment, such as area-related aid, made directly to farmers.

Good agricultural and environmental conditions: The state in which farmers must keep all agricultural land, especially land not currently used for production, in order to receive certain payments under the CAP. Includes issues such as water and soil management.

Greenhouse gas inventories: An annual record of greenhouse gas emissions, produced by each Member State and, for the EU, by the European Environmental Agency.

Greening: The adoption of agricultural practices which benefit the climate and the environment. Also commonly used to refer to the related EU support scheme.

Kyoto Protocol: An international agreement, linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, which commits industrialised countries to reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Mineral soil: Soil consisting mainly of inorganic mineral and rock particles.

Natura 2000: Network of conservation areas for rare and threatened species, and some rare natural habitat types protected under EU law.

Organic soil: Soil consisting mainly of decomposed plant and animal material.

Paris Agreement: International accord signed in 2015 to limit global warming to less than 2 °C, with every effort to limit it to 1.5 °C.

Rural development support: Part of the Common Agricultural Policy with economic, environmental and social objectives that is financed through EU, national and regional funds.

Statutory management requirement: An EU or national rule on the management of farmland to safeguard public, animal and plant health, animal welfare and the environment.

Voluntary coupled support: Optional way for Member States to make direct EU agricultural payments, based on production volumes, to farmers that choose to claim on this basis.

Replies of the Commission

Executive summary

Common replies from the Commission for paragraphs I to III:The Commission stresses that most climate- relevant measures in agriculture have mitigation and adaptation benefits which are most appropriate to be assessed together. Similarly, climate action is composed of mitigation and adaptation impacts, which in the case of agriculture cannot be clearly separated for most climate relevant measures.

IVClimate tracking was implemented for the 2014-2020 period and it was already the subject of a special report of the ECA.

The Commission reiterates its commitment to the EU approach. The method used by the Commission is sound, it has been prepared in a transparent and coordinated manner; it is based on Rio markers and it was communicated to the European Parliament and the Council.

The Commission also believes that the CAP instruments had a significant impact rather than a limited impact.

VThe Commission notes that the CAP never had the specific goal of reducing livestock emissions. Emissions remained stable, while production increased.

VIThe Commission underlines that the CAP, together with the Farm to Fork Strategy, does not only have the objective to reduce emissions but also seeks to preserve biodiversity, and rural livelihoods, reduce pesticides use and pressure on water quality and provide high quality food. Organic agriculture is one of the means to achieve all these objectives.

On grain legumes, the Commission underlines that replacing crops with high fertilization would not automatically lead to a shift of emissions to other farms. Concerning organic farming, it is not feasible to assess potential impact of emission reductions due to insufficient data available. The Commission further notes that the Farm to Fork Strategy and the Farm Sustainability Tool (FaST) for nutrients will help to reduce emissions linked to fertiliser use. In parallel, the Commission will periodically review the derogations given through the Nitrates Directive.

VIIThe afforestation support changed, increasing the maintenance support from 5 to 12 years and this period is harmonized with the payments for income loss compensation. It will make the afforestation measure more interesting for farmers. Concerning agroforestry, the Omnibus regulation made the agroforestry measure more flexible, including the possibility of renewal and regenerating of existing and deteriorated agroforestry areas, contributing to healthy development and also functioning as a carbon sink and mitigating the local microclimate. The allocation of funds (€ 64 million total public expenditure) for agroforestry is already higher than in the previous period and by the end of 2019 more than 2100 hectares of new agroforestry areas had already been established.

VIIIThe Commission considers that cross-compliance and greening scheme incentivised farmers to adopt effective climate mitigation measures.

A number of standards for good agricultural and environmental condition (GAEC) under cross-compliance are beneficial for climate mitigation and adaptation (minimum soil cover, land management to limit erosion, maintenance of soil organic matter, retention of designated landscape features) and, as compulsory practices, form a strong baseline for support schemes. Under the greening scheme, the maintenance of permanent grassland as well as the Ecological Focus Area (EFA) requires farmers to maintain areas and features such as grassland, fallow land, trees or hedges which are beneficial for climate mitigation.

IX(1). The Commission partially accepts recommendation 1a. It accepts recommendations 1b and 1c.

The Commission has taken action by including higher ambition for climate action into the CAP proposal for period 2023-2027. Conditionality has been enlarged and covers all direct payments, new eco-schemes have been proposed and 30% of the budget foreseen for rural development has been ring-fenced for climate action and environment. Member States will be laying out planned action in national strategic plans that will be assessed by the Commission.

(2). The Commission accepts recommendations 2a and 2b.

The Commission has taken action by including in the conditionality for period 2023-2027 a good agricultural and environmental condition (GAEC) related to a minimum protection of peatlands and wetlands.

(3). The Commission does not accept recommendation 3a and accepts recommendation 3b.

Member States will submit CAP strategic plans which are analysed by Commission services. After adoption of these plans, Member States will report on their implementation in yearly intervals.

Introduction

01Emissions from agriculture, as estimated according to IPCC guidelines only refer to the emissions released during the growing stage of agricultural products EU greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture are responsible for only 10% of total EU emissions. The CAP 2013-2020 does not include any lifecycle assessments for agricultural production.

Figure 1: The Commission considers that a figure representing the portion of EU GHG emissions from agriculture would be more appropriate. Such figures are readily available and compiled by the European Environment Agency’s Greenhouse Gas data viewer57.

Figure 2: Agriculture emissions by definition consist of methane and nitrous oxide and are regulated under the Effort Sharing Decision up to 2020, and under the Effort Sharing Regulation as of 2021. Land Use, Land Use Change and Forestry related emissions and removals are regulated under the LULUCF Regulation as of 2021.

04The Commission notes that emissions after 2010 stabilized, with inter-annual variation below the uncertainty threshold established by the EEA. At the same time, production has increased and emissions per unit of product have decreased.

Figure 3: The Commission considers that emissions from land are separated from the emissions of CH4 and N2O in the current climate legislation (ESR and LULUCF). Calculations of emissions of the two typologies have different characteristics and uncertainty levels.

07The 2030 Climate and Energy Framework also includes emissions and removals from the land use, land use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector. This is done via the LULUCF Regulation, which applies since the 1st of January 2021.

08Member States can design the optimal climate policy mix to achieve their national target across the Effort Sharing sectors; these strategies are described in the National Energy and Climate Plans58. Agriculture should contribute to these mitigation efforts like all other sectors. The Effort Sharing targets were calculated in line with cost-efficient considerations; if a Member State were to decide that the Agricultural sector would not contribute to the achievement of its Effort Sharing target, the contribution from the other sectors would likely be more expensive.

13The Commission considers that most tracked measures provide benefits for more than one area of interest and that any conclusion drawn with regards to the overall impact of the relevant measures should acknowledge this.

Observations

25The Commission points out that no Member States are reporting methane emissions at the highest level of detail. As also mentioned in the EU Methane Strategy, the Commission will support the improvement of the assessment and mitigation of methane emissions. The Commission notes that while livestock emissions stabilized in the last years, at the same time production increased. The Commission acknowledges the fact that livestock enteric fermentation emissions are not decreasing, though the necessary contextualization, including on the uncertainties in the assessment of methane emissions and the level of detail used by Member States when reporting, as well as the increase in productivity would better explain the situation in EU.

26The Commission considers that greenhouse gas inventory of Member States do not always detect effects of implementation of mitigation practices by farmers and which are supported by the CAP. This depends also on the setup of the monitoring systems in the Member States and the emission factors and activity data used for the estimation.

27The objective of promotion programmes is to support the competitiveness of EU agricultural sector, including the livestock sector, by raising awareness of the merits of EU agrifood products and their high production standards. The Commission underlines that the CAP has no remit to change or limit consumer’s choices.

Through their rural development programmes, Member States may offer agri-environment-climate measures supporting more extensive livestock production via extensive grazing. Most Member States use this possibility.

In addition, animal production and consumption of animal products should be considered separately, as the EU is one of the biggest exporters and importers of food and feed. The feed conversion ratio improved steadily in the past decades, i.e. one unit of animal product needs less feed input. Also within the diets of the EU livestock, inedible co/by-products from the food and biofuel industry have been increasingly incorporated.

Figure 11: The Commission considers that data on consumption should not only be related with the quantity of product but also with the quality of nutrients provided.

28The Commission proposal for the future CAP recognises the challenge of food waste as reflected in one of its specific objectives (proposed Article 6.1(i)) to “improve the response of EU agriculture to societal demands on food and health, including safe, nutritious and sustainable food, food waste, as well as animal welfare”.

30The Commission considers that new feed additives, both natural and synthetic, are very promising in reducing emissions from enteric fermentation, but with an additional cost for farmers. Several applications for feed additives aiming to reduce GHG emissions have been received by the Commission and are currently assessed by the EFSA. Subject to a positive EFSA assessment, the Commission will authorize these additives in the EU. Finally, as action within the Farm to Fork Strategy, the Commission intends to facilitate the authorization of such feed additives.

32Though dependence on direct payments is indeed high in the case of ‘specialist cattle’, it is still substantially lower in the other animal related sectors (i.e. ‘specialist milk’, ‘specialist sheep & goat’, ‘specialist granivores’, or ‘mixed livestock’). In fact, these other animal related sectors are comparable with, or even below the dependence of ‘specialist COP’ (i.e. cereals, oilseeds, protein crops).

34The Commission also takes the view that, when examining the effects of the payments on overall GHG emissions referred to by ECA, it is important to factor in the impact on global emissions (leakage) in order to show a complete picture.

To illustrate, the Jansson et al study referred to in the report (footnote 20) indeed shows that removing coupled support for ruminants would reduce total agricultural GHG emissions in the EU by 0.5%. However, it is estimated that about three quarters of this reduction could be cancelled out by emissions leakage (i.e. increased emissions outside the EU) due to an increase in imports from countries with relatively higher emissions per unit of product (emission intensities), like Brazil. This emissions leakage would significantly limit the positive impact on global warming that could come from removing coupled support in the EU.

Besides, when assessing the impact of various CAP supports on GHG, the Commission underlines that all aspects, factors and possible consequences need to be enumerated. As an example, many of the direct payments paid to animal holders might have some beneficial impacts on the environment (e.g. basic payment after pasture/grassland, greening payment, coupled support for the production of protein crops).

36While the Commission does not question the scientific article cited, it recalls that there is no officially agreed EU or International methodology to provide lifecycle assessments that are comparable. The Commission will address the environmental footprint of imported products by implementing the Green Deal and Farm to Fork objectives. In relation to the environmental footprint of imported products, the Green deal objective is to work with international partners to improve global environmental standards. Specifically, Farm to Fork envisages that “Appropriate EU policies, including trade policy will be used to support and be part of the EU’s ecological transition. The EU will seek to ensure that there is an ambitious sustainability chapter in all EU bilateral trade agreements. It will ensure full implementation and enforcement of the trade and sustainable development provisions in all trade agreements.”

The Commission notes furthermore that the majority of soy used in Europe originates from countries without deforestation risk.

38The Commission is confident that the Farm to Fork Strategy and the Sustainability Tool for nutrients will help to reduce emissions linked to fertiliser use. In parallel, the Commission will periodically review the derogations given through the Nitrates Directive.

40The Commission recalls that the CAP did not have the explicit goal to reduce livestock production and that emissions from manure are related to both quantity and management.

43Derogations to the Nitrates Directive can be granted if they do not prejudice the achievement of the objectives of the Directive. They must be justified on the basis of objective criteria, for example: