Copenhagen, 17 December 2024

Extending product lifespans helps reduce demand for new products and their related environmental impacts. This briefing aims to improve our understanding and provide novel insights on trends in product lifespans in Europe. This assessment is based on seven indicators developed specifically for the EEA’s Circularity Metrics Lab’s thematic module on product lifespans.

Key messages

- Extending product lifespans is crucial for improving circularity and sustainability by lowering demand for new materials and products. However, there is limited data on product lifespan trends.

- EU consumption increased 21% in value from 2000 to 2022 (adjusting for inflation), which implies that we are buying more and more products.

- For certain products, the average lifespan is increasing. For example, the average age of cars in use increased by 10% (from 2013 to 2022), while the lifespan of household appliance increased by 2% (2019-2023).

- Designing products to last longer contributes to extending their lifespans. An overview of selected new mobile phone models found that durability as a design feature increased by 7% from 2022 to 2023.

- Increasing intensity of use contributes to the positive impacts of extending product lifespans. For example, the use intensity of washing machines decreased by 7% from 1995 to 2020 to 23%, while several cities in the EU saw an increase of bike share possibilities.

Introduction to product lifespans

Continuously throwing away products and buying new replacements has become an unsustainable feature of modern-day consumerism. Premature disposal of consumer goods produces 261 million tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions, consumes 30 million tonnes of resources and generates 35 million tonnes of waste in the EU each year (SWD(2023) 59 final). Extending product lifespans by using them for a longer time and more intensely can help break this negative cycle and reduce the demand for new products.

Less demand in turn reduces the environmental and climate pressures related to the use of the raw materials used for manufacturing new products and can also decrease Europe’s dependency on global supply chains (United Nations Environment Programme, 2024). Using products for longer and more intensely may also lead to fewer products in circulation, which in turn reduces the volume of products being discarded and the environmental and climate pressures from waste management.

Moreover, actions supporting longer product lifespans, such as reuse, repair and share, can generate local jobs. This places actions to extend product lifespans at the very heart of a circular economy (EEA, 2024a). This importance is also reflected in EU legislation. For example, the Ecodesign for Sustainable Products Regulation (ESPR) aims to stimulate the production of and demand for more repairable and durable products.

Definitions related to products lifespan

There are various terms used to indicate the ages of products, each having slightly different interpretations:

- Lifespan (active use lifetime): the active use lifetime of a product comes to an end when it is no longer used independent of who the owner is and frequently enters an afterlife in hibernation (Murakami et al., 2010).

- Average age of devices in use: sum of the age of all devices in use, from devices which just entered the market to those coming to end of life.

- Replacement cycle: refers to the time after which a user upgrades to a new model and the old one is at the end of its first use. Such data points are occasionally misinterpreted as end of life. For example, products are often reused, either by giving them to relatives or friends, or by selling them to a recommerce platform or through a secondhand channel.

- Designed lifetime: the lifetime that a manufacturer intends its product to remain functional — shaped through design, after-sale service and other factors.

- Desired lifetime: defined as the average time that consumers want products to last.

Currently, data on product lifespans are very scarce. This briefing, which builds on a thematic module of product lifespans, assesses trends in product lifespans across Europe as a means to improve our understanding of this crucial area of circularity and sustainability. It starts with a broad picture of household consumption, then zooms in on insights for selected sectors. before looking more closely at a specific product representative of modern-day consumerism — mobile phones. The briefing also considers aspects that are relevant for lifespans, namely repair and intensity of use. It concludes with options on how to extend product lifespans.

Indicators on the broad picture

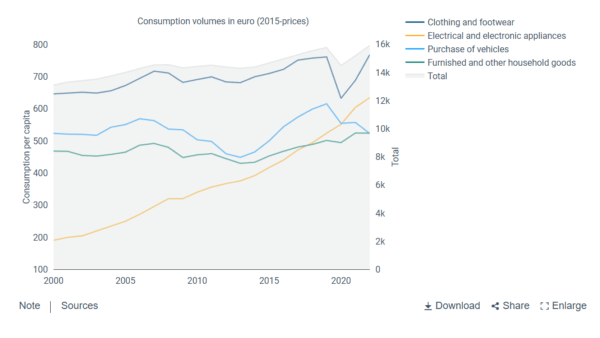

From 2000 to 2022 final consumption value per capita in the EU grew 21% (adjusting for inflation). This was partly driven by household expenditure on electrical and electronic appliances, which more than tripled during that period (Eurostat, 2024a). European households spent 25 times more on mobile phones in 2022 than they did in 2000. This surge is closely linked to the proliferation of mobile phones over the past two decades. The average European household buys a mobile phone every 2.5 years (link to Consumption fiche). The increase in overall consumption implies that we are consuming more products and that neither the lifespans nor the use intensity of products (or both) is increasing. This conclusion is supported by the lack of major reductions in material intake by the EU economy between 2010 and 2021 (EEA, 2024b).

Figure 1. Consumption volumes by domain, EU-27, 2000-2022, chain-linked volumes (2015), million EUR

Selected sector trends (mobility and household electrical goods)

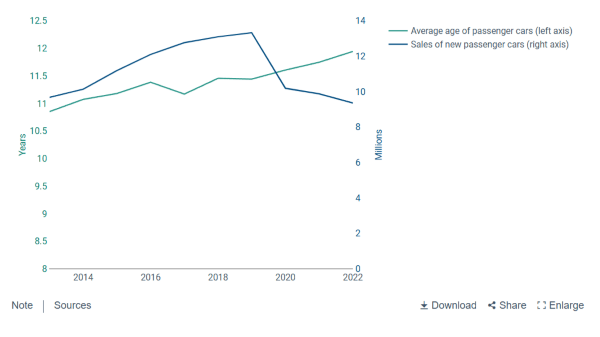

The average ageof passenger cars in the EU has increased by 10% from 2013 to 2022 (see Figure 2). In 2013, the average age of passenger cars was 10.9 years and in 2022 it was 11.9 years, according to ETC Circular economy and resource use (referencing Eurostat’s data (Eurostat, 2024d). There are regional differences and the general trend is for passenger cars to have an average age in eastern Europe that is 10 years longer on average than those in western Europe (Held et al, 2021).

The increase in average age indicates that passenger cars in the EU are remaining in use for longer periods before being replaced and thus that the lifespan for passenger cars is improving. However, this trend did not result in a reduced demand for new cars during the 2010s. Indeed, sales of new cars in the EU increased significantly from 2013 before collapsing in 2020, in part due to supply chain disruptions resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic. The decline in new car sales has continued since 2020, with inflation likely to be one limiting factor. When considering other road transport, the average age of busses is 10.8 years, while for lorries it is 8.5 years. Both busses and lorries have had stable average ages during 2013 to 2022 (Eurostat, 2024c, 2024d).

It should be noted that for products where the majority of greenhouse gas emissions come from the use stage — for example, combustion engine vehicles — extending product lifespans is not always the ideal option (European Climate Law and Regulation (EU) 2019/631). Instead, efforts should be made to find an optimal balance between lifespans and sustainable product upgrades, for example, by switching to lower emission and less polluting vehicles (Hummen and Desing, 2021). For products where the majority of emissions come from the production stage (e.g. electric vehicles), extending the lifespan is the optimal option. In other words, extending production lifespans should be done for electric vehicles, but not necessarily for combustion engine vehicles.

Figure 2. Evolution of passenger cars by age in the EU, and the evolution of the sales of new passenger cars in the EU in millions

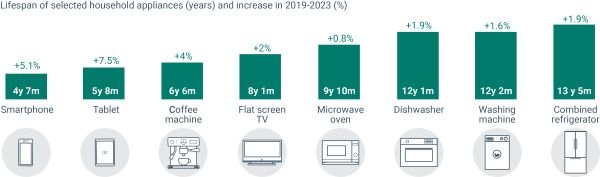

Euroconsumers collects survey data on household appliances from members (individual consumers) of the consumers organizations it gathers in Belgium, Italy, Portugal and Spain. Among the data collected are product lifespans and reasons for replacement.

From these data, we see that the lifespans of household appliances increased by nearly 2% between 2019 and 2023 (based on Euroconsumers data). Specifically, the lifespans of hi-tech appliances increased by 3% per year, over the same period, from 5 years and 8 months (or 5.6 years) to 6 years and 5 months (6.4 years), driven by an increase in the lifespans of smartphones and tablets. For small household appliances (e.g. vacuum cleaners, microwave ovens, steam irons, food processors, fryers and coffee machines), there was an overall increase of 1.2% yearly, albeit with a large spread. For example, coffee machines last on average nearly 6 years and 6 months (or 6.5 years), while corded vacuum cleaners remain operational for 10 years. Large household appliances (e.g. refrigerators, washing machines, tumble dryers and dishwashers) have the longest lifespans. For this category, average lifespans increased by 1.8% per year from 11 years and 7 months (11.6 years) in 2019 to 12 years and 5 months (12.5 years) in 2023.

When asked for reasons for replacing devices, respondents often answered that for both small and large household appliances, replacement was preferred over repair, which was seen as too expensive. For hi-tech appliances, a common reason for replacement was out-of-date software rather than malfunctioning hardware.

Overall, the data show a small improvement in lifespans for household appliances over the period in question, but that more efforts are needed to boost lifespans, specifically improving the ability to repair and upgrade products.

Figure 3. Lifespan of selected household appliances

Zooming in on mobile phones

Mobile phones have become an essential accessory to modern life. A fast-developing market with rapid improvements, upgrades and new design features provides ample motivation for consumers to frequently buy new models. Mobile phones do not make up a large segment of materials in use. Yet, the segment represents a key feature of modern-day consumerism, and the product does contain several critical raw materials.

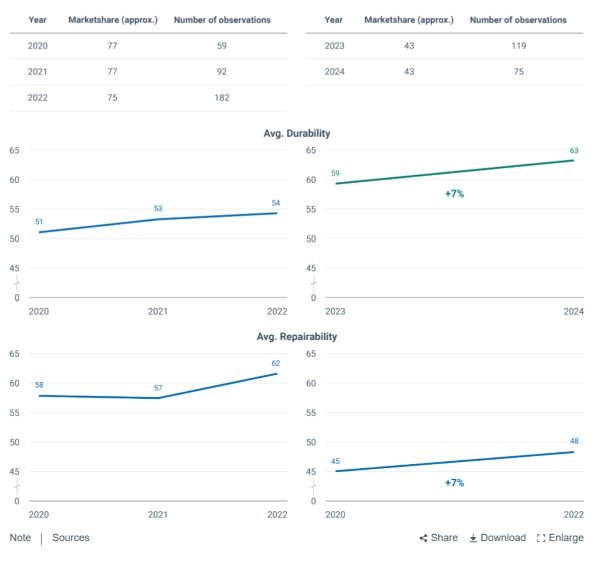

The consortium behind Eco Ratinghas developed a methodology to assess the environmental performance of mobile phones put on the market over their lifecycles. Durability is one of the key areas. It is defined as the robustness of the device, its battery life and guarantee period and its components. The more durable the device is, the less likely it is to be discarded early, potentially increasing the product’s lifespan. The overall durability score of (selected) mobile phones increased by 7% from 2023 to 2024. The devices performed significantly better on charge connector lifetime and battery life aspects, with slight improvements in dust protection. Over the same period, mobile phones scored on average better on repairability aspects such as parts and battery disassembly and on providing information on how to repair them. Low-end models tend to have a lower score on average for durability and repairability, yet they account for a higher market share.

Figure 4. Durability scope of selected mobile phones

Related indicators

Extending product lifespans is not only about keeping products for longer but also about keeping them in active use (intensity of use) to offset the demand for new products. One way to increase the intensity of use of products is to share them between users. To investigate this aspect, we have analysed options for bike sharing in selected European cities and how consumers use washing machines as two examples of this aspect.

Bike sharing

The availability of shared bikes in eight European citiesincreased by 4% between 2016 and 2023. Two cities (Brussels and Vilius) saw a decreasing trend, while growth was especially driven by four cities (Ljubljana, Lund, Luxemburg and Lyon). The selected cities with the highest share of rental bikes had an average of 1.75 rental bikes per 1,000 inhabitants (or approximately 7 bikes for every 4,000 inhabitants), while those with a lower share had 0.75 rental bikes per 1,000 inhabitants.

Washing machines

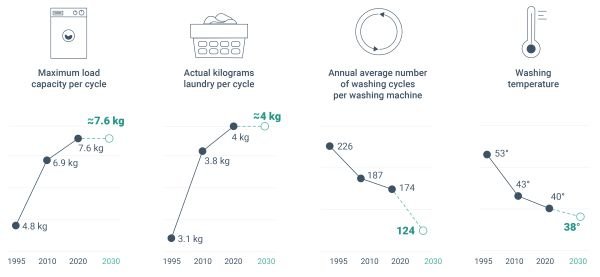

For washing machines, there was a 7% decrease in the intensity to 23% decrease of use (how often washing machines are used) in the EU from 1995 to 2020 (ETC CE based on EC, 2023). The maximum load capacity of washing machines in Europe has increased from 4.8kg/cycle in 1995 to 7.6kg/cycle in 2020. However, the actual average laundry amount per cycle remains lower than the capacity, rising more slowly from 3.1kg/cycle (65% of capacity) in 1995 to 4kg/cycle (53%) in 2020. Similarly, the average number of washing cycles per machine has decreased from 226 cycles in 1995 to 174 in 2020. The decrease in cycles can be attributed to smaller household sizes, leading to more individually owned washing machines. On a positive note, the average wash temperature decreased from 53°C in 1995 to 40°C in 2020, which represents a saving in electricity use. The total annual laundry volume in the EU-27 rose from 95 billion kilograms in 1995 (131kg/per person) to 121 billion kilograms in 2020 (265kg/pp) (EC, 2023). Overall, these trends indicate that Europeans are putting more clothes per cycle in washing machines but use less of their maximum capacity, and while the stock of washing machines has increased, Europeans tend to use them less intensively.

Figure 5. Trends and forecast for washing machine use in the EU

After a period of stagnation (2013-2015), the number of employees in the repair sector increased between 2015 and 2017 from about 191,000 to about 203,000 respectively. Since then, the number of employees decreased to about 177,000 in 2020. The negative trend seems to have stopped for repairs made in the ‘personal and household goods’ category, which registered a small growth in jobs in 2021, the most recent year for which statistics are available. The decline in employees active in the ‘repair of computers and communication equipment’ category has continued to 2021, in line with general economic trends.

There is evidence that at least one-third of European consumers have not repaired their most recently broken products (EC, 2018). The unavailability of spare parts and the increased complexity of products are other important barriers to repairing products (EC, 2018). In the coming years an increase in repair activity is expected due to the EU’s ‘right to repair’ rules and other regulations.

Circular options for extending product lifespans

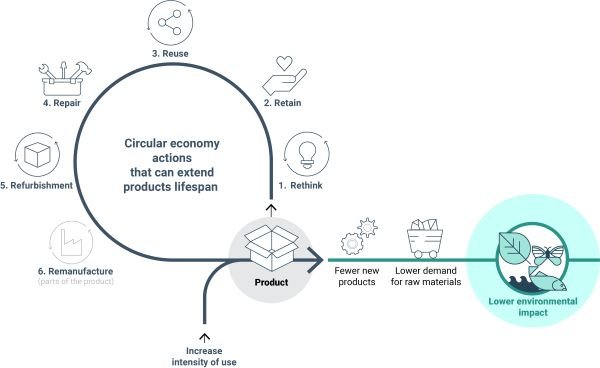

There are several circular economy actions that can extend product lifespans (EEA, 2024a).

Figure 6. Options for extending product lifespans and their environmental benefits

The ‘rethink’ strategy includes the initial design decisions that can affect the durability, reusability and repairability of products. The ESPR contains performance and information conditions that can help consumers buy longer lasting products and provide incentives for producers to consider measures to extend lifespans. The rethink strategy also includes changing business strategies, for example by moving to a product-service-systems approach, which potentially increases the intensity of use. Design can also include not just the technical features of products but also an enhanced emotional durability so that consumers want to keep them in use for longer.

The ‘retain’ strategy can extend product lifespans during the use stage. Careful use and preventive maintenance are important actions by users or service providers to ensure products are suitable for their purpose for the maximum time. Technical issues such as planned obsolescence and the removal of technical support for older products should be discouraged. There is a similar need to resist social and cultural pressures, often from marketing campaigns, to replace well-functioning products with new products.

The ‘reuse and share’ strategy can ensure that when one user no longer requires a product it can continue to be used in its original function by others. In reuse cases, ownership is transferred from one user to another (for example between friends and family), sold on (online) markets or donated to charity. In sharing cases the product does not change ownership, but an arrangement allows for multiple users.

The ‘repair’ strategy can help prevent products from simply being discarded when they break. This extends their lifespans and keeps material and resources in the economy for longer. Obstacles to the repair approach, such as high costs and complexity, are increasingly being addressed through initiatives such as the ‘right to repair’ rules. Related strategies include refurbishment and remanufacturing, which also enables materials and resources to be used for longer, albeit with significant changes to the product and its components.

More efforts will be needed to change behavioural aspects, increasing trust in repaired and upgraded items and not making ‘buying new’ the default option. Further data are also required to enable a more detailed understanding of trends in product lifespans and measurement of any rebound effects or other system failures. Moreover, extending lifespans does not always equal a one-to-one displacement of new products. Instead, the money ‘saved’ from not needing to replace a product should not be used to buy a completely different product, which would lead to a rebound effect (Zink and Geyer, 2017).

Source – EEA